Background

Bilateral donors channel a large share of their development assistance through multi-partner financing mechanisms/multi-partner funds, or MPFs. When bilateral funds are transferred to MPF administrators, donors become at least one step further removed from implementation on the ground.

MPFs are often used in conflict-affected situations or for addressing global challenges. In both cases, framework conditions for the MPF administrator are complex, posing challenges for managing the funds well. At the same time, donor agencies remain legally accountable to their own national authorities for the application of the funds. The eight funding partners for the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre – Australia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK – therefore supported a review of this issue.

The funds

To identify vulnerabilities to corruption risks in MPFs, the analysis has to be based on specific funds so that the risk picture can be as concrete as possible. For this reason, this review has looked at policies and practices in MPFs that represent important channels for donor funding. These constitute case studies both for how donors relate to multi-partner funds, and how the various administrators address the possibilities of funds abuse.

The team requested information from the U4 donors regarding which MPFs they had financed during the five-year period 2012-2016 with at least US$5 million. While completeness of information varied, some donors finance a wide range of MPFs but with markedly varying levels of support. The team therefore decided to focus on funds that most of the donors supported, which are the larger and better-known ones, ending up with the following six funds:

- ARTF – Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund.

- LOTFA –Law and Order Trust Fund for Afghanistan.

- CERF –Central Emergency Response Fund.

- GPE – Global Partnership for Education.

- Gavi – Global Alliance for Vaccines.

- GFATM – Global Fund to fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Virtually all eight donors support all six funds, as shown in Table 2.1 below, as there are only a couple of cells that are not crossed off.

Table 2.1: Engagement in funds, by donor

|

Fund |

AUS |

DEN |

FIN |

GER |

NOR |

SWE |

SWI |

UK |

|

|

UNDP1 |

LOTFA |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

|

UN Sec/OCHA2 |

CERF |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

World Bank |

ARTF |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

World Bank |

GPE |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Global Fund |

GFATM |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Gavi3 |

Gavi |

* |

* |

|

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

Source: Information on the respective trust fund web-sites. 1.UNDP: United Nations Development Programme. 2.OCHA: UN Office for the Coordinator of Humanitarian Affairs. 3. Gavi: Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization.

These six funds cover a range of dimensions that are important for understanding the various forms of risk that MPFs face:

- Diversity of funds structure: ARTF, LOTFA, Gavi, and CERF have a standard structure with a decision-making body – board or steering committee – that is composed of some of the parties to the fund, supported by an administrator that acts as trustee (treasurer) and technical secretariat to the fund. In some funds, that same organisation may also play a role on the implementation side. GPE and GFATM, on the other hand, are Financial Intermediary Funds (FIFs). While a FIF also has an independent board that makes policy decisions, the roles of trustee, administrator/secretariat, and implementing partners are more clearly separated, providing for several different constellations, as presented in section 3 below.

- Diversity of administrators: Four of the funds are administered by multilateral agencies – though this status also varies somewhat. ARTF, LOTFA, and CERF are administered directly by the World Bank, UNDP, and OCHA, respectively. GPE, as a FIF, has the World Bank as trustee and the secretariat is hosted by the World Bank, even though the World Bank sits outside its organisational structure and acts as an independent body. Gavi is an independent fund and thus has contracted its own secretariat. GFATM, as a FIF under the World Bank, has also acquired a very independent status for its secretariat and is in practice largely an independent fund answering to its board on most matters, but still has a fiduciary responsibility towards the World Bank as trustee.

- Distribution of administrators: Two funds are thus managed by the World Bank, two by the UN system – UNDP and OCHA – while Gavi and GFATM are largely independent.

- Country specific versus global: Two of the funds – LOTFA and ARTF – are country-specific funds, in the same country but with two different administrators. The other four have global remits.

- General versus thematic: Four of the funds are thematic – Gavi and GFATM in health, GPE in education, LOTFA in internal security/police and prison services. ARTF and CERF are not sector-specific but can finance activities in any sector that the parties to the funds agree to.

- Emergency versus development: CERF is the largest standing fund for humanitarian needs, while the other five are more classic development funds. They provide a mix of virtual budget support (civil service salaries in ARTF and LOTFA, consumables with Gavi and to some extent in GFATM and GPE) and/or grants funding for projects (ARTF, GPE, Gavi, GFATM).

- Vulnerable versus stable environments: ARTF, LOTFA and CERF are set up to work in conflict or otherwise vulnerable environments, while the other three funds work in stable as well as vulnerable situations where the range and nature of vulnerabilities vary considerably

Each of these funds is furthermore among the largest or is the largest in its ‘category.’ CERF is the largest fund for humanitarian assistance, GPE the largest education fund, and GFATM the largest health fund. The ARTF is the largest single-country fund and one of the longest-functioning ones, having been established in 2002. LOTFA is only one year younger, and is the largest MPF for the security sector, which is a notoriously difficult sector in terms of transparency and accountability.

The contributions to each of these funds by the eight donors over the last six years are shown in Table 2.2 below, which total nearly US$16 billion. These funds thus constitute important channels of donor funding.

Table 2.2: Total funding to the six funds, by donor by year, in US$ ‘000

|

All Funds |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

Total |

|

Australia |

222,348 |

254,154 |

319,384 |

182,976 |

175,981 |

104,808 |

1,259,651 |

|

Denmark |

127,799 |

123,666 |

127,386 |

86,368 |

78,400 |

75,331 |

618,950 |

|

Finland |

26,702 |

28,226 |

32,659 |

26,001 |

24,108 |

20,531 |

158,227 |

|

Germany |

425,927 |

431,558 |

516,144 |

407,504 |

560,598 |

806,208 |

3,147,939 |

|

Norway |

345,449 |

362,973 |

374,518 |

365,410 |

346,198 |

395,191 |

2,189,739 |

|

Sweden |

222,474 |

303,976 |

357,760 |

205,793 |

312,058 |

274,028 |

1,676,089 |

|

Switzerland |

21,764 |

25,171 |

37,697 |

46,025 |

33,352 |

49,328 |

213,337 |

|

UK |

881,150 |

995,193 |

1,138,837 |

1,238,279 |

1,029,114 |

1 283,810 |

6,566,383 |

|

Totals |

2,273,613 |

2,524,917 |

2,904,385 |

2,558,356 |

2,559,809 |

3,009,235 |

15,830,315 |

Source: Annex C

The relative importance of these funding levels as against these donors’ total aid varies considerably. Using data from the OECD aid database, Table 2.3 shows total aid by donor by year for the five years 2012-2016 (the 2017 data are not yet available) and the share in percent that the six funds in total represent of the aid for each.

These six funds received a total of 6.42% of all aid from these donors over this period: nearly US$13 billion out of a total of US$200 billion in aid. This is a significant share and shows the importance of multi-donor mechanisms as channels for bilateral aid.

When looking at relative importance, Norway and the UK channel around 10% of their aid through these six funds, while Switzerland has also kept the share stable, but only at around 1% of its total aid. Denmark and Germany seem to be decreasing their use of these funds in relative terms, while Australia and Sweden appear to be increasing theirs.

It should be noted, however, that the relative importance of these six funds compared to the total amounts that donors channel through all MPFs is unknown. During the five-year period 2012-2016, Norway funded over 60 MPFs in the World Bank with more than 5 million Norwegian Kroner each, and around 55 MPFs through UNDP. In addition there are a number of one-off, small-scale contributions under the 5 million Norwegian Kroner limit through the multilaterals. But Norway has also contributed to other MPFs, such as the Syria Recovery Trust Fund, which was administered by Germany’s KfW, so the total amounts through MPFs in the case of Norway is considerably higher than just for the six funds included here. The situation for the other donors in this regard is unknown, but presumably provides a similarly complex picture.

|

|

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|

Australia |

Total aid |

4 540 |

4 149 |

3 498 |

2 752 |

2 290 |

|

Funds % |

4.90% |

6.13% |

9.13% |

6.65% |

7.68% |

|

|

Denmark |

Total aid |

1 921 |

2 134 |

2 130 |

1 880 |

1 654 |

|

Funds % |

6.65% |

5.80% |

5.98% |

4.59% |

4.74% |

|

|

Finland |

Total aid |

795 |

822 |

937 |

698 |

638 |

|

Funds % |

3.36% |

3.43% |

3.49% |

3.73% |

3.78% |

|

|

Germany |

Total aid |

8 584 |

9 451 |

11 589 |

14 113 |

19 636 |

|

Funds % |

4.96% |

4.57% |

4.45% |

2.89% |

2.85% |

|

|

Norway |

Total aid |

3 522 |

4 315 |

3 889 |

3 306 |

3 451 |

|

Funds % |

9.81% |

8.41% |

9.63% |

11.05% |

10.03% |

|

|

Sweden |

Total aid |

3 638 |

3 917 |

4 343 |

4 827 |

3 452 |

|

Funds % |

6.12% |

7.76% |

8.24% |

4.26% |

9.04% |

|

|

Switzerland |

Total aid |

2 453 |

2 506 |

2 778 |

2 726 |

2 773 |

|

Funds % |

0.89% |

1.00% |

1.36% |

1.69% |

1.20% |

|

|

UK |

Total aid |

8 665 |

10 517 |

11 231 |

11 718 |

11 517 |

|

Funds % |

10.17% |

9.46% |

10.14% |

10.57% |

8.94% |

Source: Table 2.2 above and OECD IDS data.

Funds management and corruption risks

Multi-partner funds cover a range of administrative and implementing arrangements, as noted above. One of the major differences is between single-country versus global funds since the global funds face a multitude of different country contexts and thus a more complex risk picture. The single-country funds are first, followed by the global funds.

Country-specific funds

The two single-country funds in Afghanistan, though working in the same risky environment, nevertheless face quite different implementation risks. The more complex one is the ARTF, though the more risk-exposed one is likely to be the LOTFA, as explained below.

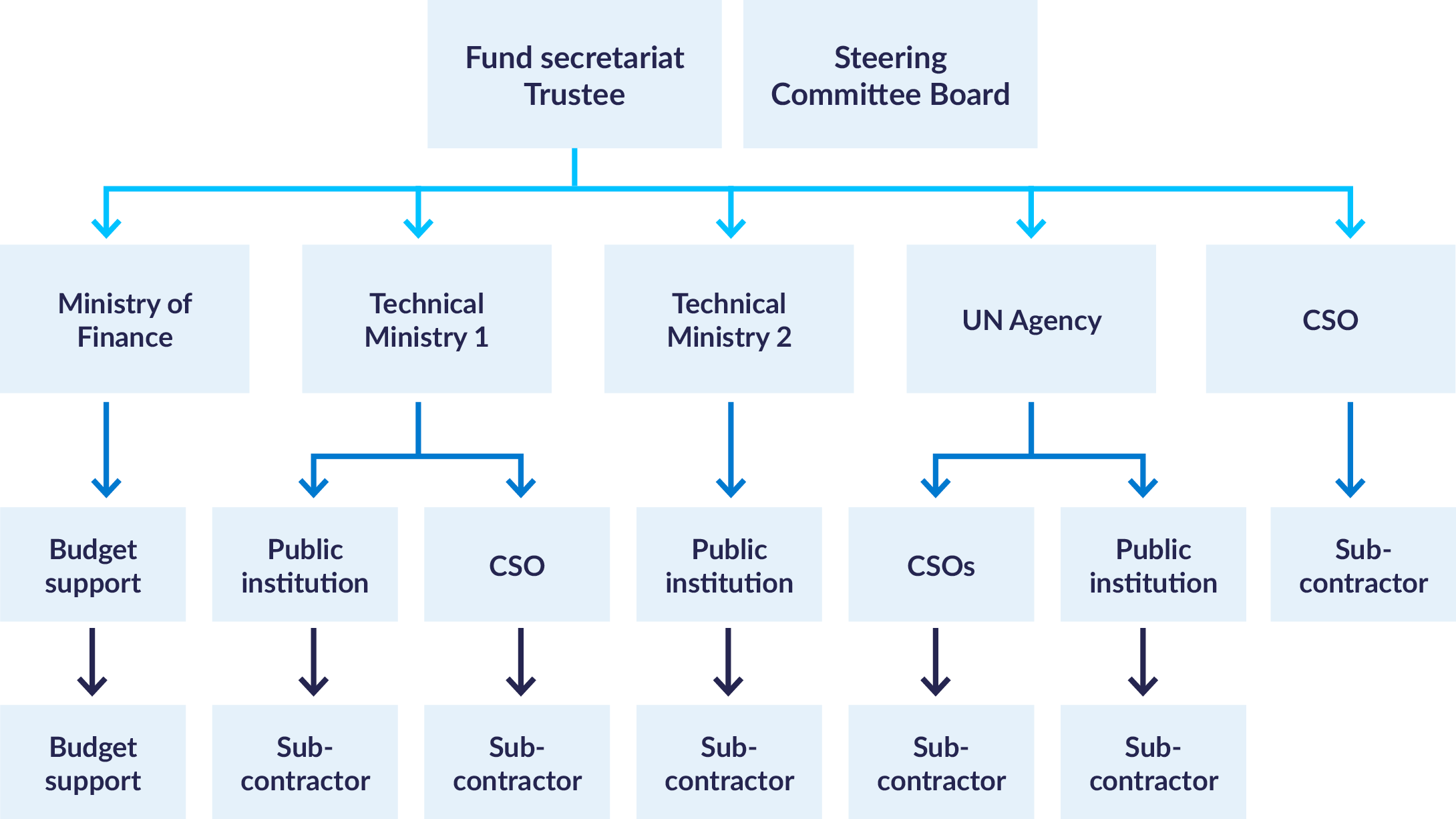

Figure 3.1 shows the possible structure of a country fund, which in fact looks quite similar to how the ARTF is structured. The World Bank is trustee and administrator of the fund and chairs the decision-making bodies: a Steering Committee that sets policies, and a Management Committee that takes the funding decisions. Total annual disbursements hover around US$800-900 million.

ARTF funding is provided in two forms: as budget support that goes to the Ministry of Finance (MoF), and as project financing that is channeled through line ministries. For project funding, however, a wider range of implementing partners could become involved, such as UN agencies and CSOs.

Figure 3.1: Schematic structure, country specific fund

From this general picture, the financing streams may then follow different paths. Budget support is the direct responsibility of the MoF, and in the case of the ARTF goes largely to fund civil service salaries in the social sectors as well as some ‘free funds’ for Government priorities on the budget. The World Bank tracks the performance of these funds in part by hiring a third-party Monitoring Agent (MA) that carries out document-based compliance verification. The MA ensures that funds are only used for the purposes agreed to, and that documentation for these expenditures are according to Bank procedures and the Government’s own rules and regulations.

Project funding has primarily gone to large national programs either in the social sectors – health and education – or for rural development, such as a national community development program and a rural roads program. The ministry responsible for the sector can then implement the program itself, as largely happens in the education sector, or it can contract out (some of) the work to local actors such as CSOs or UN agencies, as is done in the health sector. These implementation partners may in turn have local sub-contractors to deliver services in, for example, difficult-access areas. The implementation model can thus vary, using a mix of some direct public and some contracted non-state actors. In addition to the Administrator’s own monitoring, verification of project performance is outsourced to a Supervisory Agent (SA), which uses a number of methods to document that contracted infrastructure is in fact built, built to standard, and – increasingly – also verifying that it is being used as intended.

LOTFA, on the other hand, is limited to funding the security sector – police and prison services – and disburses US$300-400 million per year, largely for salaries. LOTFA, however, provides support to what is internationally recognised to be among the most opaque sectors in a public administration, and which in the case of Afghanistan is notoriously corrupt.

LOTFA has in principle a simple delivery chain, since UNDP is trustee, administrator and also retains the quality assurance functions. Steps have been taken to address classic challenges such as weeding out ‘ghost workers,’ minimising transfer losses by paying directly into recipients’ own bank accounts, etc. This has reduced some of the direct abuses in the system. A number of studies by the UNDP itself, the US Special Inspector-General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), and others note that corruption is endemic to these services, and that this has also been true with respect to LOTFA funding, leading UNDP to step up its internal controls, expand oversight personnel, and put more senior staff in charge.

At the same time, the Afghanistan funds address the overarching risk factor of the extreme degrees of corruption embedded in the public sector by having this as core concerns of the funds. The manner in which they manage this, however, remains largely related to direct funds management – that is, the fiduciary risk is tackled through controlling the disbursement flows as far as the administrator has a mandate to do so. The end result for intended beneficiaries of the financing is normally addressed through monitoring systems and reviews that are not linked with the fiduciary control instruments, however, so corruption risk management and performance management are far not fully linked.

Global/thematic funds

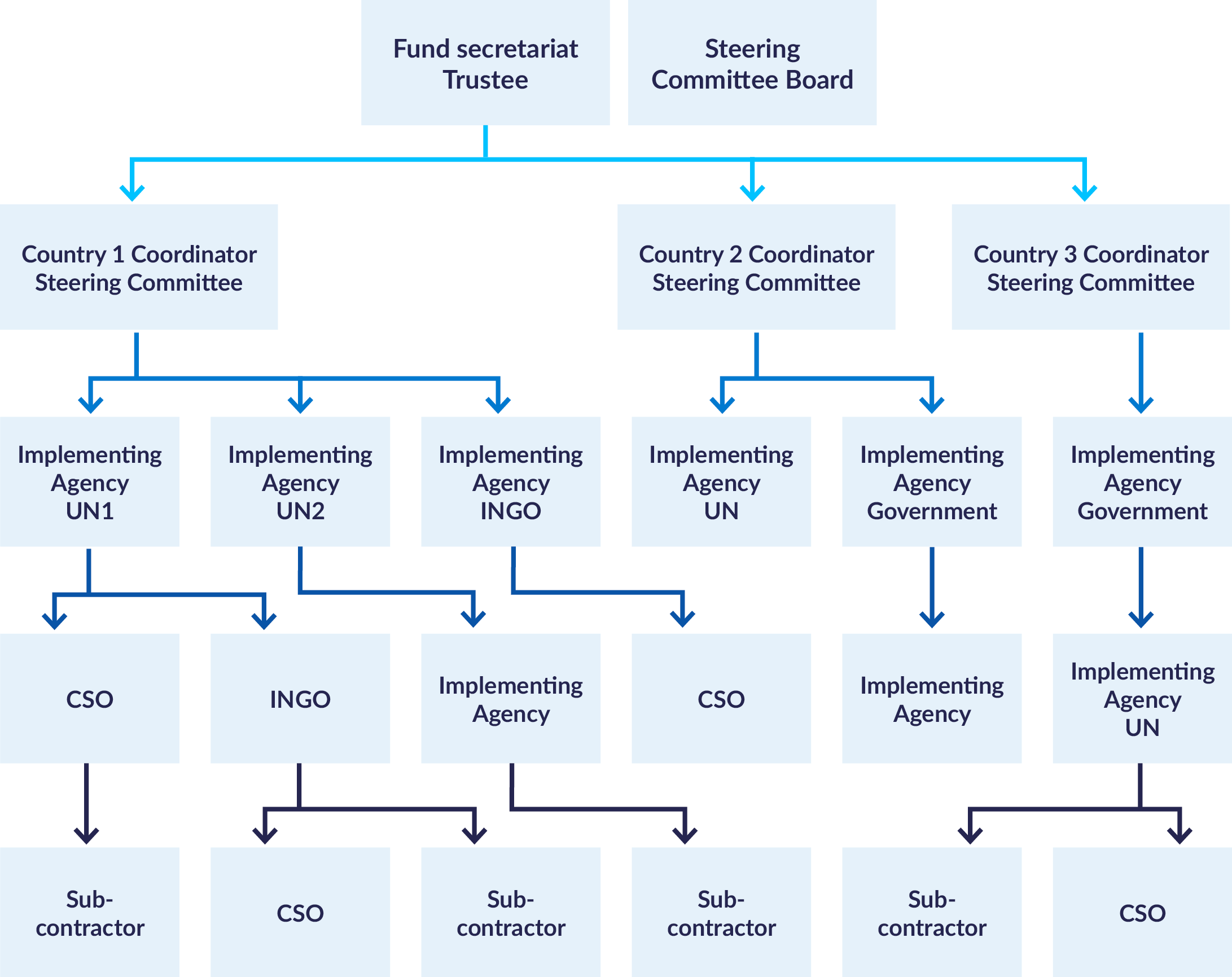

Global funds generally add a couple of layers of complexity to their structures, as seen in Figure 3.2 below. For country-specific funds, the functions of trustee, administrator, and main advisor/implementor is usually handled by the same actor, as noted above for the Afghanistan funds.

For the larger global funds, however, these functions are often separated, as noted above. This by itself may not increase the risks to the donors as the decision-making bodies tend to have similar multi-partner memberships in which donors have a significant voice. The real differences between global funds and country-based ones are that global or thematic funds finance activities across a wide range of country contexts and also tend to be more accountable for end-results since they were set up for specific objectives. This has shaped the structuring of their delivery chains.

The CERF faces a particular situation of having to respond within days to the occurrence of a disaster, whether man-made or natural. UN OCHA normally coordinates, oversees and controls these funds since doing so falls within its mandate and since it typically already has a presence on the ground where getting resources quickly to affected populations and regions is paramount.

The other funds address a mix of capacity-building and service delivery in a particular sector. These are medium- to long-term concerns. They therefore establish a national body that agrees upon criteria for selection of activities, proposes or decides which to fund, monitors and reports on the performance of the activities, and assumes general financial oversight responsibilities. These national bodies normally invite donors represented in-country to participate. In the case of GPE and Gavi, it is the national ministries of education and health, respectively, that chair the national coordination bodies, while for GFATM the body that chairs the national coordination varies depending on country situation. This is in part due to the somewhat differing mandates of the three funds and how these mandates are perceived. While GPE and Gavi are addressing national educational and health programmes, the GFATM is addressing specific diseases. How these can best be addressed is something that is discussed at the country level given the context. The GFATM thus ends up with a more complicated delivery system when looked at from a global perspective.

Figure 3.2: Schematic structure, global/thematic funds

The changing fund landscape

The more recent funds – Gavi, GFATM, and GPE – have embraced a more open approach to both management and implementation arrangements. Boards have wider representation that may include civil society and other non-state actors like private foundations. The major shift, however, is to a greater role for non-state actors for delivering the services to intended beneficiaries, as there is a clear focus on delivering results even under challenging situations. This is for example reflected in GFATM’s third strategic objective, ‘Promote and protect human rights and gender equality,’ which treats these issues as fundamental to successfully addressing the overarching objective of ending AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria as medical epidemics. GFATM handles these issues in this way because these epidemics typically affect groups that may be marginalised along one or more dimensions – gender, ethnicity, age, and geography – so that more complex and comprehensive approaches to addressing medical epidemics are required. This in turn means that a wider range of stakeholders beyond donors and the host government need to become involved.

In principle each delivery chain results from an analysis of which actor has a comparative advantage in delivering best value for money in a given context at each step in the chain. The contracts along the chain should in principle all contain the delivery standards that the fund administrator requires for releasing financing, which invariably includes rules designed to prevent fraud and corruption. But while a sub-contractor is accountable to the body preceding it in the chain, the actor awarding a (sub-) contract also is expected to ensure that the sub-contractor has the experience, capacity, and systems in place to deliver the results and according to the stipulated conditions, including by carrying out a due diligence process. The standard of operations and the duty of care which each operator is to follow is in principle to be the same along the entire chain. The reality on the ground, of course, is that this may not always be possible: local CSOs operating in difficult environments will not have the same capacities and safeguards that a UN agency can put in place.

The vulnerability to corruption risk along the various delivery chains are thus in part a function of how many steps there are in each chain, since each hand-over point opens up for contracts and agreements that may contain weaknesses, not least of incomplete due diligence verifications of the next actor in the chain. But the weaknesses are even more a function of the reality regarding the capacities that the last link in the delivery chain has, as well as the complex environment in which that actor is trying to deliver its services, often to hard-to-reach beneficiary groups. Delivering health services to a poor family in rural but stable northern Mozambique is very different from trying to reach poor families in conflict-ridden southern Afghanistan, and the administrative and risk management costs of ensuring the same level of service delivery integrity are obviously different. And here comes the real challenge for the funds that have clear end-of-the-line delivery obligations: there is often a trade-off between reducing fiduciary risk versus the risk of not being able to deliver the results.

Risk appetite

The actual risks for resource abuse depend on what is being delivered, financing or direct services. The ARTF and LOTFA provide large sums directly to pay for local services such as salaries and basic running costs of key organisations. Gavi provides mostly in-kind vaccines and supplies that often have little value on the private market. Some of the medications that GFATM provides may have alternative uses and thus may end up on local parallel markets.

When it comes to local purchases/contracting, the sums involved in national contracts are much higher than in local procurement of goods and services. While the selection process for national contracts is normally more rigorous, where there is (partial) state capture, local elites will try to steer contracts in particular directions through manipulating the procurement system, applying increasingly sophisticated means that may be difficult for formal procedural instruments to uncover. Small-scale local contracting may run into more obvious short-comings, such as limited number of eligible suppliers, where eligibility may be for formal or informal (corrupt) reasons. Deciding what represents ‘value for money’ may become highly context-dependent: if the only way to deliver life-saving health care is to accept ‘access payments’ to local strong-men, the imperative of saving lives may go before the ‘zero tolerance’ of partial funds mis-direction.

Most funds help pay for capacity development and/or hiring of local staff. The main challenge is the selection of candidates, where donors want a meritocratic and relevant selection process while the actual process may be dominated by nepotism, clientelism, and other forms of favouritism. In many societies, being hired by a foreign-funded organisation or participate in a training may bring a range of benefits, and these activities are therefore often controlled by patronage systems that are difficult for external actors to see and understand.

All the funds have whistle-blower/complaints systems for reporting suspicions or cases of fraud and embezzlement that protect the identity of the person or persons reporting. The follow-up appears to vary, where Gavi and GFATM have staff with police and security sector experience, while the World Bank and in particular the UN have been somewhat slower in including such investigative skills. For the donors, the UN system poses particular challenges due to its single audit system: since UN agencies are inter-governmental bodies, they cannot be subject to audits by external non-state actors. Particularly if UN staff members are directly involved in a case, information is generally only provided once the case has been fully investigated and concluded, a process that may take years. The more independent funds are much more transparent about such cases and will share information also during the process if this is of relevance to other actors’ work. But there is clearly increased attention to this field by all actors, where reviews of UN agencies point to more professional and pro-active internal controls and audits, and the UN Office of Internal Oversight Services has stepped up its oversight and control.

UNDP’s Multi-Party Trust Fund Office (MPTFO) provides a number of tools for the design, management and control of multi-partner trust funds (see designing pooled funds for performance manual, among others). It presents principles for designing a risk management strategy (RMS) and provides examples of how to go about elaborating the RMS, where the determination of the risk tolerance and thus the risk policy of the fund is important. The office manual is somewhat more cursory when it comes to the actual guidelines for setting up MPFs and where more of the focus is on fiduciary risk (MPTF Office Manual for Fund Design, Administration and Advisory Services, December 2014). The World Bank also tracks fiduciary risk, in part because it sees this is a comparative advantage when pitching its MPFs to donors, since donors remain concerned about this issue and thus want to be sure that fiduciary systems and reporting are in place and credible.

The more independent funds Gavi and GFATM have more elaborate risk management policies and have produced explicit risk appetite materials for discussion and decisions by their Boards These provide a structured breakdown of what are considered the main risk sources (procurement, grant oversight and compliance/country management capacity, etc.), provide an analysis of causes, and then some rating of the current risk – an exercise that is generally done at the portfolio level but can be carried out also at country or programme component levels.

A major concern for all the funds is the activities in conflict or fragile societies, where public sector capacity is weak and/or political will to address problems is poor. Capacity development is thus critical, yet the solutions chosen may themselves be problematic. While the World Bank, by mandate, must work with governments, and Gavi and GPE as sector funds have the strengthening of national (public) systems as core to their missions, GFATM in some countries may find that relying on national health ministries hampers more than supports successful implementation. Its fourth objective, ‘build resilient and sustainable systems for health’, may thus in the first instance focus on the actual service delivery points rather than on national systems. This poses the classic trade-off dilemma of short-term efficiency of service delivery to hoped-for medium-term effectiveness through strengthening overarching (national) systems.

On the other hand, while Gavi has ‘sustainable transition’ as a separate risk-element – and requires all partner countries to build-in exit and transition strategies – GFATM does not, pointing to a key risk element that most of the funds do not treat well.

The UNMPTFO manual and Gavi present a standard risk assessment matrix – likelihood/probability of occurrence mapped against consequences – to provide a risk profile. In the case of Gavi, this matrix is used to identify the level of risk that Gavi should be able to accept by risk source, but then also identify which risk factors need to be addressed. GFATM uses a similar approach. Both funds end up with a risk picture, and then present an analysis of the situation and where they would like to be a given period from now. This becomes the basis for discussions by their Boards both regarding the risk acceptance levels – the risk appetite – but also on their risk management strategy – which risks they would like to focus on, to reduce overall risk exposure.f10184343b2f

Both funds, however, carry out the analysis in light of what the overarching objectives for the funds are, so risks are discussed in light of possible trade-offs against their substantive goals.

For both funds, this is a recent discussion, and it has not been an easy one. A key reason is that it requires that the donors engage and accept that the funds face risks that cannot be reduced to zero. This is not incompatible with a ‘zero tolerance for corruption’ policy, but entails a willingness to share responsibility if and when a problem actually occurs.

Donor approaches

In 2016, the OECD’s Council for Development Cooperation agreed a set of 10 recommendations on how to address corruption risk and how to respond to actual instances of corrupt practices in development cooperation (see Box 4.1).

This builds on the more general work the OECD has developed over the years, where the 2011 Convention on combating bribery of foreign public officials in international business transactions is a key contribution. These have been followed by a series of guidance notes, including for sectors that are particularly vulnerable to corruption, such as the extractive industries.

The eight U4 member countries have been among the active contributors to this work. These OECD standards and guidance represent an international consensus and ‘good practice’ standards. They are also the foundations for the eight donors’ own anti-corruption policies and practices.

Box 4.1: OECD: Managing the risk of corruption – recommendations

The OECD 2016 report recommends that countries establish a 10-part anti-corruption system that can be summarised as follows:

Code of Conduct or equivalent for all relevant public officials, endorsed by the highest authority within the agency, disseminated to all staff and communicated on an ongoing basis, that clearly establish what practices should be avoided and embraced with regard to corruption and anti-corruption, respectively.

Ethics or anti-corruption assistance/advisory services available to provide ethics and anti-corruption advice, guidance and support, ensure that staff providing such advisory services are trained and prepared to discuss sensitive matters, and build trust between staff responsible to providing advice in anti-corruption with the rest of personnel.

Training and awareness raising on anti-corruption, which should include ethics/anti-corruption training, also for locally-engaged staff in partner countries, clarify roles and responsibilities of different staff, and assure that training includes corruption risk identification, assessment, and mitigation approaches as well as main international obligations.

High level audit and internal investigation that includes both internal and external audit services based on internationally agreed standards, investigatory capacity to respond to audit findings, systematic and timely follow-up of findings to ensure that weaknesses are addressed and sanctions applied.

Active, systematic, on-going multi-level assessment and management of corruption risks, where corruption risk assessment is integrated into programme planning and management cycles, assuring analysis and review of risk throughout the project cycle, provide guidance appropriate for different levels of corruption risk analysis, using tools like risk registers and update them throughout implementation, strengthen integration between agency control functions, and build an evidence base for corruption risk management by sharing experiences widely.

Measures to prevent and detect corruption enshrined in ODA contracts: Ensure that funding is accompanied by adequate measures to prevent and detect corruption, ensuring that applicants are subject to due diligence prior to granting ODA funding, and specifically prohibit implementing partners/sub-contractors from engaging in corruption.

Reporting/whistle-blowing mechanism: This is applicable for all public officials and implementing partners, with clear instructions on how to recognise indications of corruption and on the steps to take if indications of corruption arise, assuring broad accessibility of secure reporting mechanisms, communicating clearly how confidential reports can be made, with alternatives to the normal chain of management or advice services, ensuring protection for whistle-blowers, and communicating clearly and frequently about the processes and outcomes of corruption reporting.

Sanctioning regime, that should include termination, suspension, or reimbursement clauses or other civil and criminal actions, where applicable, have in place a sanctioning regime that is effective, proportionate, and dissuasive with clear and impartial processes and criteria for sanctioning, and allowing sharing information on corruption events.

Joint responses to corruption to enhance effectiveness of anti-corruption efforts: Agree in advance on a graduated joint response to possible cases of corruption, following the partner government lead where this exists and promoting transparency, accountability, and donor coordination where this lead is absent, encouraging other donors to respond collectively, fostering accountability and transparency including publicising rationale for/nature of responses to corruption cases, and acting internationally in upholding anti-corruption obligations.

Take into consideration the risks posed by the environment of operation: Performing in-depth political economy analysis where context allows so that development interventions are designed with adequate anti-corruption measures and does not inadvertently reinforce or support corruption, working with recipients and grantees to improve their risk management systems, and with key government departments to improve joint efforts to fight corrupt practices.

Source: Recommendation of the Council for Development Co-operation Actors on managing the risk of corruption

All eight donors have formal policies and response mechanisms that are in accordance with the OECD recommendations and guidelines. Furthermore, the multilateral agencies also participate in this work and hence adhere to these standards in their own policies and principles. There is therefore no substantive difference of opinion between the bilateral donors and the multilateral organisations that typically administer MPFs when it comes to the priority of addressing corruption.

The differences among the donors lie to some extent in how they operationalise these principles, and to what extent they emphasise prevention and strengthening of local systems and capacities to address the corruption risk versus tracking money flows and requiring accountability for usage. The greater differences seem to lie in how they apply their rules and procedures, in particular how they respond to possible cases of fraud and embezzlement (does size/scale of missing funds matter?); how strict they are about requiring restitution of funds lost; and what are the consequences for the administrators of these funds.

While donors therefore appear to have developed fairly clear principles and practices in cases of corruption, the more recent discussions on ‘risk appetite’ with some of the MPFs do not seem to have found their way into formal donor policies and instruments yet.

Norway and multi-partner funds

To exemplify the challenges MPF administrators face, the case of Norway as an MPF financing partner can be instructive.

Norway channels an increasing share of its development resources through MPFs. This is in part for political reasons, as supporting and strengthening the multilateral system is an important aspect of Norway’s foreign policy. But it is also for pragmatic reasons: the multilateral system addresses a wider range of issues and reaches a larger universe of eligible beneficiaries for Norwegian aid than Norway could on its own. Equally important, this is done at lower administrative cost than if Norway were to manage these funds directly. A particular benefit for Norway, as a fairly small donor with limited presence in some of the fragile states that are a political priority, is that through the MPFs it can participate in high-level policy discussions, get access to information and share its views with a much wider range of actors at much higher levels than it otherwise would have been able to. MPFs like the ARTF thus are efficient mechanisms for addressing aid effectiveness concerns, often providing national authorities more voice than they would have if they were to address each donor separately, thus also supporting local ownership. For donors, MPFs also reduce the risks of engaging in highly volatile contexts by having a more experienced and capable administrator manage the funds and by having the costs and risks shared among a larger community of donors.

At the same time, the total portfolio of MPF engagements is spread across a number of technical units and departments in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and Norad. Roles and exact responsibilities are not always clear, which makes it difficult to ensure similar approaches and practices across the different MPFs.

This fragmentation of MPF engagement is not unique to Norway. Other U4 partners such as Germany, Sweden, and the UK also distribute responsibilities for MPFs across different units within their aid administration. Risk management then becomes complicated, since the different units within Norway’s aid management system, for example, have different mandates and need to respond to those rather than taking an overarching MPF approach.

As in other donor countries, the political imperative of addressing corruption in a forceful manner means that Norway strictly adheres to the ‘zero tolerance’ policy. When it comes to funds that are under direct Norwegian responsibility – bilateral aid, support through Norwegian NGOs or Norwegian business – the policy is clear: as soon as there is a suspicion of possible funds abuse, a preliminary assessment of the case should be initiated, no matter the amount involved. Once there is documentation that supports such a suspicion, the MFA should choose the response it finds most appropriate, given the size and seriousness of the cause of the possible fraud. If there is a reasonable suspicion of funds abuse, no matter the cause, all payments to that beneficiary are stopped. Furthermore, funds that can be shown to have been abused should be returned to Norway, so the recipient partner must refund all misused funds, whether or not they themselves are able to reclaim from those who actually are responsible.

When it comes to Norwegian financing of MPFs, the issue is somewhat different. As with any donor, it is the overarching agreement between the donor and the administrator of the MPF that is primary. In the case of the UN system, donors have signed general agreements regarding issues like the single audit principle. While MPF funding must respect this, donors may ask if the MPF administrator has satisfactory preventative and control measures in place, with monitoring and response systems that address the donor’s demands for zero tolerance. Donors require that the MPF spell out control and follow-up mechanisms in the signed agreement or that references be made there to the organisation’s general rules and principles.

Given these framework conditions, recent discussions with MPF administrators regarding the risks of funds abuse focus on modifications to the templates that underlie the MPF agreements. Revised templates affect largely upcoming agreements since they cannot have a retroactive effect, but if existing agreements are revised the new template language would be used. Over the years 2016-2017 MPF administrators agreed upon new agreement templates with main UN agencies and large parts of the World Bank. Once a fund agreement has been developed and signed, it is however complicated to amend since the agreement is a consensus document based on the negotiations with all the interested parties to the fund. The ARTF has over the years had a total of 34 donors, all of which have signed the trust fund agreement. Amending it becomes a time-consuming affair, and something that a funds administrator would therefore like to avoid or minimise. The more recent special-purpose funds that have been set up as independent foundations or organisations are thus in some sense simpler. They do not have the agency’s history and existing rules that may constrain how the fund is structured. But while Gavi and GFATM secretariats are recent bodies, they are both headquartered in Switzerland and thus have been set up under Swiss law. For donor lawyers it thus required that they understand relevant parts of Swiss legislation that could explain choices made regarding the governance, oversight, and control of the organisation, as well as its funds and activities.

There are thus a number of ‘hidden’ transaction costs and possible risks to Norway and other donors when funding MPFs instead of their own internal organisation, legislation, and political concerns.

Looking ahead

With increasing levels of donor funds channeled through a growing universe of MPFs, some of which use quite tailored and thus complex arrangements for delivering results, donors face a range of risks that may be difficult to gauge.

The recent modifications to the basic agreement templates with most multilateral agencies have addressed a number of the direct funds abuse concerns, and have harmonised approaches and expected responses to identified cases of fraud.

The discussions at the boards of Gavi and GFATM regarding their respective risk management strategies and risk appetite is a further step towards a more holistic understanding of risk, both along the delivery chain to the end user, but also linking risk directly to the achievement of fund objectives. Seeing possible trade-offs between risk taking and results achievements provides a more realistic approach to managing risk, not least of all by making risk a collective responsibility among all the stakeholders to the fund, and not simply an additional administrative and reputational cost to the administrator.

While not unique to these funds – the UN MPTFO guidelines include these same principles, as noted – the systematicity and implementation of such an approach holds promise for how to better manage risks in complex mechanisms working under difficult framework conditions.

The changing environment

While aid is becoming a less important share of total funding available for the financing of the SDGs, it is still critical to a number of societies battling poverty, disease, and conflict. The improved efficiency and effectiveness of aid resources thus remains critical as a pillar of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda for financing the SDGs.

Given the increased share of aid that goes to address fragility, conflict, and global public goods, it is likely that the role of MPFs will increase since donors want to contain their own administrative costs and risk exposure when aid is directed to less predictable, more unstable, and thus more costly operating environments.

At the same time, many regimes in these societies are becoming more authoritarian, representing particularistic and narrow economic interests. Their ability to shield illicit resource flows and rent-seeking is increasing, while the space for civic action is being increasingly constrained. This puts additional demands on the administrators of funds who are tasked with addressing issues and reaching beneficiary groups that may not represent core concerns of national authorities.

MPF administrators and boards therefore often face an increasingly challenging reality on the ground. More active participation and direct risk sharing with a larger community of donors may thus also be important for MPF administrators for managing the larger risk of the operating environment.

Accepting and managing risk

Better and more sophisticated management of available resources through joint mechanisms – collective action in the face of governance failure – is therefore seen as an appropriate response. The challenge is finding models for joint action that are internally cost-effective while delivering on their development objectives, given that operating environments are known to contain wildly differing degrees of risk.

Donors have tended to focus on fiduciary risk, in part because media highlight direct funds abuse (‘corruption scandals’), leading MPF administrators in the World Bank and UN agencies to concentrate on this. The ‘zero tolerance’ approach carries with it an expectation of restitution and some form of sanctioning of unacceptable behavior, which has made MPF administrators direct considerable resources to this field. While there is agreement that funds abuse is an important issue that should be tackled diligently, there are actors in the international community who believe a disproportionate share of administrative resources is being allocated to this.

The sector funds are instead pushing towards a more broad-based understanding of total risks to successful achievements. They are open to including a wider range of actors in the analyses, decisions, and delivery of services. This provides for more flexibility but also exposes the funds to potentially more forms and points of funds abuse along the delivery chains. More sophisticated risk tools and using more, better, and more timely data are opening up possibilities for identifying and addressing forms of risk at an earlier stage and allowing more actors to provide relevant information for better decision-making. The more directed and sophisticated compilation and analysis of information, the sharing of ‘lessons learned,’ and more active dialogue with stakeholders along the various delivery chains all contribute to providing management with better understandings of the nature and dangers of various challenges, thus providing the respective boards with better foundations for their decisions. One particular concern, noted above, is that a focus on flexible and efficient delivery may push towards solution sets that may have strong local anchoring but weak national ownership, so the risk of such an approach not being sustainable may become an increasing issue.

While more, better, and more timely information and analysis is being provided, this does not necessarily reduce risk, especially since rent-seekers will always find new avenues for grabbing resources once one access point has been closed. Acceptance of this dynamic risk picture and the fact that risk is in fact quite high is important: Gavi’s overall risk profile is heavily skewed toward the ‘highly likely/high impact’ risk corner. But once that picture has been prepared, presented, and discussed, the stakeholders have been willing to accept the realism of the risk picture, and have agreed upon actions to be taken to manage and reduce risk exposure, as a joint commitment.

Given that stakeholders seem to be moving in a direction of greater acknowledgement of the actual risks inherent in these joint mechanisms and the environments in which they largely function, a number of options are available to donors for managing their own risk exposure.

Summing up and looking to the future

Donors are increasing their focus on fragile and conflict-ridden situations. At the same time, the demands for documenting the results from this aid are growing. While these pressures may not be fully compatible, MPFs have become a vehicle-of-choice for bridging the two, for a number of reasons:

- The ‘classic’ MPF administrators – the multilateral agencies – were set up exactly to work in difficult environments, and thus have legitimacy and experience in such work.

- MPFs are good vehicles for addressing the concerns of the aid effectiveness agenda – the Paris Declaration, the Accra Agenda for Action, and the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation – where all now have SDGs as their overarching objective and are aligned with the Addis Ababa Action Agenda for the financing of the SDGs.

- MPFs have formal agreements with the donors, in many cases updated based on negotiations, taking on board more current concerns and requirements by policy makers in donor countries.

- MPF administrators have considerable political access and legitimacy on the ground, creating an arena for dialogue and thus possibilities for harmonising donor efforts while allowing space for national actors to take ownership and leadership – all of which are common policy concerns of donors.

- MPFs provide professional management, institutional solidity, oversight and control procedures, and capacity that provide donors the fiduciary assurances that legislation requires.

- MPFs, as a pooling mechanism, allow for risk sharing and, in principle, benefitting from the various partners’ comparative advantages in a given context.

- MPFs are often ‘best in class’ when it comes to transparency and accountability regarding finances and activity results, particularly when compared with what individual donors are normally able to provide in terms of documentation and insight into demanding environments.

- Donors retain real influence by participating on central boards and often on country-based committees of the various funds, thus gaining opportunities to both shape and challenge the MPFs activities and the results produced.

While MPFs thus exhibit a number of features that are of great value to bilateral donors, particularly for smaller ones who cannot possibly finance the administration of complex operations under difficult circumstances, MPFs also pose some challenges:

- The multilateral bodies that act as administrators for MPFs – development banks, UN agencies – do not have MPFs as their primary ‘line of business,’ yet MPFs are administered according to the Administrator’s rules and procedures. These rules and procedures may not always be the most appropriate for fast-moving and unpredictable situations. There may thus be a trade-off between perceived fiduciary solidity versus efficient and effective delivery.

- While MPFs in principle should lower donors’ transaction costs, some efficiency gains may be lost due to the internal fragmentation of MPF responsibilities within the donor organisation itself: the division of labour between ministry, directorate, and embassy, and between various policy and technical units. Ensuring coherence, consistency, and completeness in managing MPF funding may thus require considerable internal coordination efforts.

- MPF management costs are also escalating for the multilateral administrators. UNDP has addressed this with the establishment of a separate Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office in their New York headquarters, whereas within the World Bank and other development banks, MPF management may be split across technical, geographic, investigative, and administrative units. There is therefore work going on to try to rationalise and decrease the number of trust funds, since there has been a proliferation of these over the years, largely driven by donors wishing to pursue particular development objectives in part by mobilising joint funding through an MPF.

- The division between financial versus results performance remains a gap in the funds that are administered by the multilateral agencies. Resource mobilisation and reporting has tended to be a responsibility towards the donor while results performance has been targeted toward the individual activity funded and reported to a wider and more general audience.

- Because of their mandates and in particular the UN agencies being inter-governmental bodies, the multilateral agencies have focused on working with the public administration. As a result, they continue to face challenges when wanting to include private sector actors, civil society, foundations, and academia on the policy setting, fund raising, or implementation sides. This is because the systems and procedures internal to MPFs provide some stumbling blocks to more open and inclusive partnerships and thus barriers to efficiency and effectiveness measures.

- The organisational status provides for some differences that are difficult to overcome: the World Bank is a membership organisation with an independent board and can thus challenge a national government on its management of support. UN agencies are ‘owned’ by all member-countries of the UN, and thus have a more complicated link to national authorities. That is why they tend to resort to nudging more than pushing changes when performance is unsatisfactory.

- The specialised funds that are set up to address more clearly articulated end-states – GPE, Gavi, GFATM – have a mandate to pursue these, and thus are in the enviable position of being able to insist on solutions to possible delivery problems.

- These differences between funds due to administrator or mandate then have consequences for how risk is defined and addressed, as noted above.

- Perhaps the greatest challenge is that MPFs often represent considerable resources, particularly in fragile and conflict environments, and thus are tempting targets for rent-seekers. While first-order disbursements from funds usually are tightly controlled, the subsequent use of funds – for local purchases, construction, hiring, etc. – is typically where funds abuse occurs. In most settings, this is at a point in the delivery chain where the fund administrator or other international actors are no longer directly involved, so control and insight are weaker. The legal issues thus become complicated, yet the ramifications of local nepotism, patronage networks, and contract capture may be severe for the intended results. While end-of-state funds see this is a core issue, standard MPFs that provide funding for local actors to implement their priorities face both policy and practical issues if they try to address such concerns.

- For MPF administrators, it is also problematic that some donors have limited knowledge and experience with the actual implementation challenges they face. One fund administrator noted that donors who participates in periodic reviews or evaluations in the field are much more appreciative of the constraints and choices that administrators and implementers face, and that this provides for more constructive dialogue on how to move the fund forward.

- The experience of some funds administrators and implementing partners is that there is an increasing focus on audits, compliance verification, risk avoidance, and placing risk and responsibilities on actors that may not be in a position to shoulder these.

Looking ahead, donors to MPFs may therefore consider the following options:

- Donors should clarify with MPFs what the actual end-states are that the funding aims to accomplish, so as to hold all actors involved accountable for performance.

- In light of this, donors should challenge MPF administrators with regards to how participatory and inclusive the MPF in fact is when it comes to needs identification, policy and priority setting, quality assurance of financial and performance results and reporting, and implementation

- Donors should encourage a risk analysis of the funds’ actual delivery chains, followed by a discussion on stakeholders’ risk appetites, in order to agree an action plan for addressing priority risks and to ensure a joint commitment to sharing those risks.

- Donors should review resource levels dedicated to corruption prevention versus investigation and prosecution of possible fraud, among other things to avoid a disproportionate share to prosecutorial activities.

- Donors should review their responses to cases of fraud, to ensure that the response is proportionate to the problem identified and preferably addressed to the actor or actors actually responsible for the problem.

- The U4 donors may consider setting up a joint learning approach for managing MPF risks. One could select two of the funds, such as ARTF and Gavi, and finance a comprehensive risk analysis and mitigation strategy for the ARTF, and with Gavi extract lessons from its risk appetite process as a starting point for reviewing their own policies and procedures for managing MPF risks.

- Finally, U4 donors may review their MPF policies and procedures to minimize possible inconsistencies and in particular try to harmonize their risk management understandings and approaches, to reduce the overall transaction costs of channeling resources through MPFs.

- While the UN MPTFO guidelines provide the same approach, since it is a generic model for all the various trust funds under UNDP administration, it does not provide actual risk analyses, whereas Gavi and GFATM present the actual risk factors, risk assessments and risk mitigation proposals for their respective Boards to discuss.