EITI and pathways to improve natural resource governance

Conceived in the late 1990s and launched in June 2003, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) has been a hallmark of international resource governance efforts. Initially designed as a voluntary process of extractive sector revenue disclosure for payments between companies and governments, the EITI evolved in the 2010s into a broader instrument seeking to improve transparency and accountability along the whole natural resource management value chain, including corporate beneficiary ownership. Under its 2019 Standard, the ambition of the EITI is to further broaden this disclosure, including for contracts and environmental impacts, to contribute to more developmentally effective extractive resources exploitation.

The EITI is generally considered a success story, given the large number of resource‑dependent governments that have committed to it and the vast support it has received from donors, non‑governmental organisations (NGOs), and extractive industry companies.87fb0f6bed0a Yet, after more than a decade of implementation, many researchers, practitioners, donors, and decision makers are asking what the EITI’s impact on resource governance and development has been so far, and whether the EITI assumption that information disclosure brings about change is indeed valid. As a result, donors, practitioners, and many of the studies evaluating the EITI have called for an explicit Theory of Change (ToC) as it could help understand how the EITI is expected to result in better extractive sector governance and improved development in participating countries.d97e9783b2c0

Although the EITI Board established a working group to develop a more rigorous and realistic results framework,2d35057cdf0a the EITI Secretariat has long been reluctant to formally establish a ToC. Its Deputy Head and Executive Director have argued that it is more important to focus on the small wins than the large overarching goals, and that having a specific ToC might scare some countries off.7e0f23143e56 It was only in 2019, under the leadership of the new EITI Board Chair, Helen Clark, that discussions restarted on the EITI ToC, and it is now included in the 2020 EITI International Secretariat Work Plan.18ebf3ae7512 Subsequently there is greater interest in defining a ToC and understanding how the EITI could help improve natural resource governance and developmental outcomes.

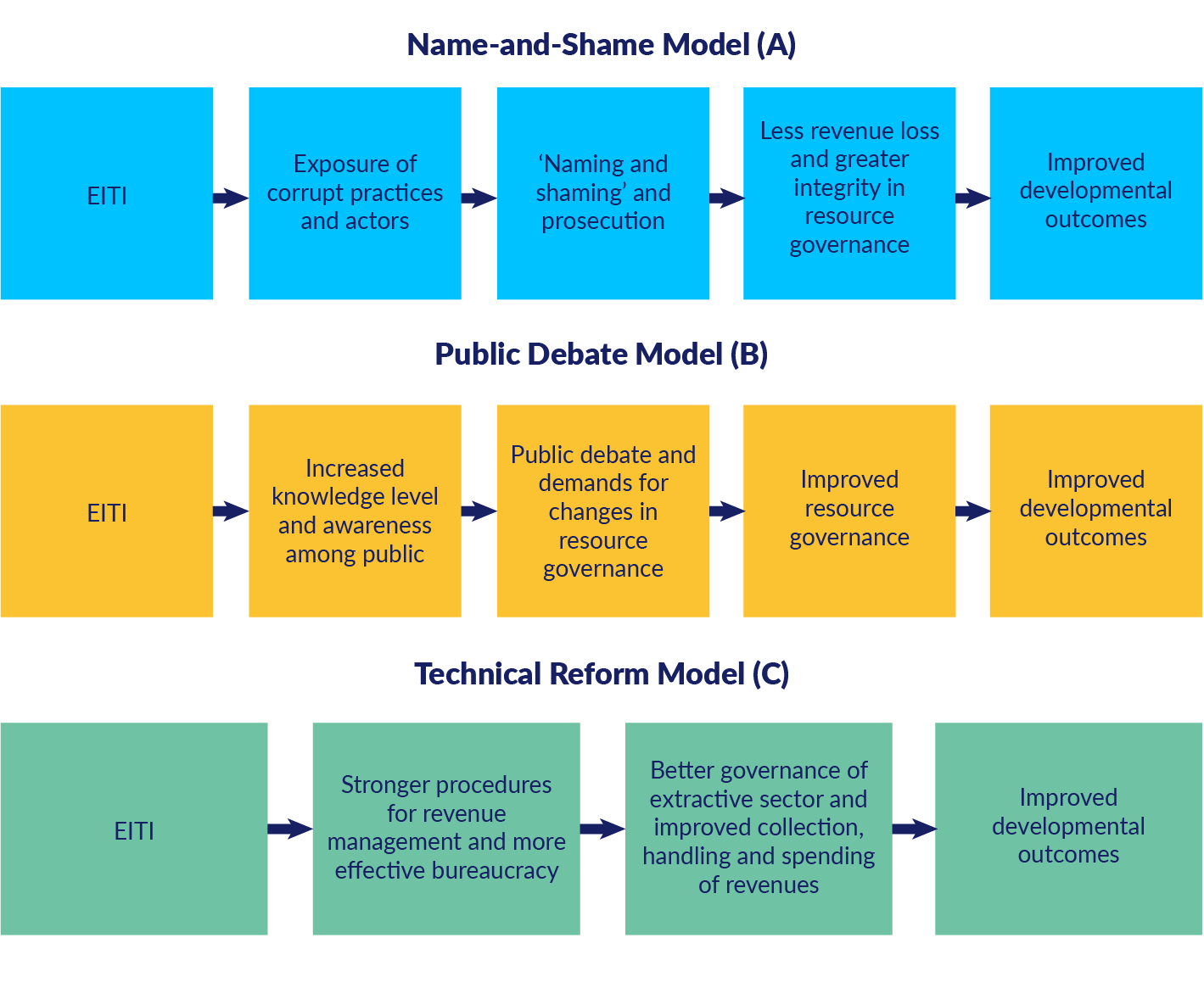

Based on previous literature, a survey, three country case studies, and our own observations from a decade of engagement with the EITI,cbc20b43176d we introduce three simplified and stylised models on how the EITI can reach its long-term goals of improving natural resource governance and promoting inclusive forms of social and economic development. These are: 1) Naming and shaming, ie pointing out stakeholders that are mismanaging or stealing natural resource revenues, including through investigations and prosecution, to curtail revenue loss and increase integrity in resource management; 2) Public debate, ie increasing knowledge levels among the public and public demand for better resource governance, to change and improve natural resource governance; and 3) Technical reforms, ie strengthening the procedures and efficiency of the bureaucracy dealing with natural resources, to improve the collection, handling, and spending of revenues. Although the three models are not mutually exclusive and can be complementary, they are useful in structuring reflections and discussions about how the EITI and information disclosure can lead to better extractive sector management and improved developmental outcomes for the society.

Our findings point to the value of a ToC approach for the EITI, although the suitability of the three main models varies from country to country and, over time, within a country. We identify the need for national and international EITI bodies to work together to design and implement ToC models that are best suited to local contexts, including governance and development issues. We emphasise that there is no one EITI ToC, but rather that each model is context specific (depending on the challenges that each of the EITI implementing countries faces) and should be grounded in the EITI Principles. Based on the interviews conducted, there is a need, and desire among the stakeholders, for the EITI International Secretariat to start helping the implementing countries in developing and instituting country-specific ToCs.

Theory of Change

A Theory of Change (ToC) is often referred to as programme theory, pathway mapping, programme logic, road map, or direction to travel. There is no consensus around a specific definition of what a Theory of Change (ToC) is, but broadly it can be described as a way to understand how an intervention will lead to a specific change.7c4af81db9fa Its aim is to connect outputs and activities of an initiative (such as the EITI) to the desired outcome(s). The ToC describes the set of intermediary steps through which short-term activities and outputs will lead to the achievement of long-term goals.e5076eb3c1c5

The concept of ToC was introduced in the 1990s, partly as a reaction within the development organisations against the logframe methodology – a tool for project planning, monitoring, and evaluation, which is more rigid and linear. The logframe had become a mandatory requirement for many donors, serving as a constraint for the implementing organisations, and was seen as an instrument for donors to control projects and programmes, with at times counterproductive effects. In contrast, ToC models have been promoted as having a stronger potential to better understand the complexity of change processes.29a5f823d391 Mayne6341db703db6 argues that a ToC helps to better identify the assumptions and interlinkages within a causal chain – or impact pathway – and thus understand how to move from one step to another. These could be changes coming directly from a specific intervention or from external and unanticipated influences.

A ToC can serve many purposes, such as developing common understanding, bringing greater clarity, effectiveness, and focus, as well as providing a framework for evaluation and monitoring, organisational development, communication, and more generally empowering stakeholders.a3c48fa9e8cf Stein and Valters1c3c2c28435a argue that ToC should be understood as a continuum. At one end it can be a practical planning tool, and at the other end, it is a complex understanding of how things change to help policymakers and practitioners become more ‘political[ly] literate.’ In between these two extremes, is the process of describing how a project is expected to work – in less rigid ways than just the ‘planning toolbox’ but also in less complex ways than a full ‘political literacy’ approach. Stein and Valtersbe43357cd3c8 identify four main purpose categories for ToC: 1) Strategic planning, 2) Monitoring and evaluation, 3) Description, and 4) Learning. These categories are overlapping, and an organisation does not have to use ToC for all of these purposes.

Most organisations with an aim to make change have a ToC, whether it is stated or implicit. However, to understand how a ToC functions within an organisation, it is useful to look at how it is implemented at different levels of the organisation. James06c5af62f9ef defines several levels at which a ToC can work, including macro level, sector or target group level, organisational level, and project and programme level. Stein and Valterscab7089db19e point out that it often can be difficult to identify at which level the ToC should be implemented, or whether it is necessary at all levels. If the latter is the case, a unified theory would be required, which would be an enormous task. On the other hand, only implementing it at specific levels might make it one-dimensional.

Ownership of the process is important. Sullivan and Stewart42f1af2c94b9 argue that it is essential to develop a ToC which takes into account the specific context in which the project will be implemented. They suggest that ‘total ownership’ is the ideal, where all stakeholders are engaged in developing and evaluating the ToC. In the case of the EITI, this would require a consensus within the EITI community (ie members and participants across the world as well as within participating countries).

Transparency, accountability, and natural resource (revenue) governance

The transparency narrative

Theories of transparency often model it as operating through a causal chain where information disclosure catalyses a series of phases ending in improved governance, and in which each stage acts as a prerequisite for the following stage.46da65d6a28c Formulated as a ‘transparency action cycle’,f78a4a53527d the transparency process in the extractive industry context would consist of the state, or the EITI, disclosing information about natural resource (revenue) management that will be used by the public to form or amend views, to debate resource related issues, and, when necessary, as a basis for voicing concerns and requesting improved accountability in natural resource management. The state would respond constructively to such action and feedback through changing its practices and policies. Better governance is then expected to increase the revenues available for education, health care, infrastructure, and other sectors that promote societal development. The loop would be finalised by the state/EITI providing updated information to the public about the changes for further evaluation.

A fragile process

The ‘change through transparency’ process described above appears as fragile as its weakest link. First, transparency may fail if the information provided does not reach the intended audience (ie the ‘public’ for the EITI, see discussion below).fbe65b1e2436 Information disclosure may have a disempowering effect on already marginalised people as it can empower already better-off groups or individuals.1acd40153c831af3cdaba001

Second, transparency may also fail if it leads to what can be called the ‘illusion of transparency’:bb2e710a32ae governments and other actors are believed to be transparent as they make information public (nominal transparency), yet do not follow through on disclosing relevant or sensitive information.569617563c80 In some cases, limited information disclosure may be used by authorities to reduce (well-founded) distrust and suspicion among citizens, therefore (problematically) supporting the status quo in cases where effective change is needed.b2af538090b9

Third, for attitudinal and behavioural changes to take place, the public must find the information they receive useful, care about the information and the policy in question, and be dissatisfied with the status quo. Further, in order to request improved natural resource governance, citizens need to have feasible ways of acting on the disclosed information, and they need to be aware of what those are.

Finally, it all depends on the state’s response being constructive, adequate, and open for making structural changes in governance. It is important to remember that if prior to disclosing information on the extractive sector, a ‘public’ that demanded improved natural resource (revenue) governance had not emerged, perhaps it is unreasonable to expect that such a public will emerge following the release of such information unless other measures are taken simultaneously to support the transparency process.

Overall, evidence from studies on the impact of information on behaviour is mixed and inconclusive, even in the cases where the issues related to children’s education and health and, therefore, were of more immediate, personal interest for the target audiences.caafaf46aada There are many possible reasons for the low levels of behavioural changes when it comes to information disclosure, such as people having more important needs to attend to; thinking it is not their responsibility to request change but rather that of their representatives, civil society groups, other prominent (educated) figures, and even foreigners; not being able to act on the information provided to them since it may be too costly or beyond their means to do so; or being afraid of reprisals.d6297c4e2529

Who is the public?

A key issue in understanding how and why the transparency process functions (or does not function) in extractive industries, is the ill-defined ‘public’ so often evoked in transparency discussion,6517f174eb90 and EITI Principles and the series of EITI Standards issued since 2003 (see Annex 2). Who exactly is the public? Does it refer to a wide range of intermediary organisations such as civil society organisations (CSOs), media, and supreme audit institutions on which the transparency literature places high expectations when it comes to accessing, interpreting, and disseminating information to the citizens?41cca844c50f Or is it the mass of ‘ordinary’ citizens who are expected to hold their representatives accountable through elections or other (equally ill-defined) methods after they have been presented with information regarding extractive industry management?

These questions are not trivial as the answers have great consequences when it comes to what information to disseminate, to whom and through which channels, and what, often poor and not highly educated, citizens are supposed to do with the information. While a few committed individuals may suffice to push for local changes, attempts to change national resource governance policies and practices would most likely require collective action by citizens to hold the state accountable directly (through elections or other means) or indirectly (through official oversight bodies). However, there are examples of national extractive sector reforms that have resulted from the initiatives of individual leaders or administrations, international pressure, commercial imperatives, or other motives aside from citizen collective action. In many cases, there are various intermediary organisations that, given an opportunity, can fulfil the role of the watchdog on behalf of the public. Examples of these include national and international NGOs, and even state institutions tasked to conduct audits and pursue any inadequacies or wrongdoings they uncover.4560973f9000

Alternative impact pathways

Whereas the dominant transparency narrative is built on a relatively narrow and fragile pathway linking disclosure, public mobilisation, and government response, other impact pathways are possible.aa30c03f1bf5

First is the contribution of the EITI to the diffusion of a global norm of greater transparency in governance, including financial and contractual aspects, across a wide range of organisations, including companies and governments. By legitimising and normalising transparency beyond its own process, the EITI has made a broad contribution to the ‘good governance’ agenda. Within its own realm, the EITI may have helped to see the emergence of mandatory reporting laws in the EU, Canada, and beyond, notably by setting precedents and facilitating discussions between different stakeholders.

Such impacts can be seen, for example, in the voluntary disclosure of trading data by some commodity trading companies that were previously very secretive. Some extractive companies are also voluntarily disclosing their contracts and beneficial ownership. At the government level, a number of authoritarian governments joining EITI have to better acknowledge that resources are the property of the public, not of the ruling elites. These impacts have not made governance accountable overnight, and progress has remained marginal in many difficult contexts; yet, they remain valuable and point to the need for a broader assessment of the governance impact pathway of the EITI.

Second is the deterrence impact of transparency processes. As the idea and practice of transparency spreads through various government agencies and companies, some bad practices and poor decisions may be prevented. Assessing deterrence impacts is difficult, but lack of solid evidence should not be seen as lack of impact and greater attention is needed to assess deterrence as an impact pathway across our three models.

Third is the cross-stakeholder dynamics that often result from the nature of transparency processes such as the EITI. Multi-stakeholder initiatives create opportunities and foster interactions which contribute to exchanges of concerns and perspectives that would otherwise take place in more polarising settings, such as public demonstrations. The EITI multi-stakeholder processes have not only contributed to such exchanges between CSOs, companies, and governments. In many cases they have also helped consolidate the capacity, knowledge, and networks of participants – especially CSOs, which in turn have been able to provide more effective support across a wider range of issues in the extractive sector. Although, we note that in some cases CSOs feel that they were distracted, if not in part co-opted, by these processes.

Beyond extractive sectors, the EITI multi-stakeholder component has further emphasised the importance of opening civic space, especially in countries where extractive companies and international financial institutions did not want to push such a ‘political’ agenda (eg Azerbaijan and Equatorial Guinea).e70df318318d More attention should also be given to this multi-stakeholder governance impact pathway.

The evolution of the EITI

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) was officially launched in June 2003 by the then British Prime Minister Tony Blair, largely as a result of Global Witness’ ground-breaking campaign to end corruption in war-torn oil-rich Angola (1999). The EITI was designed as a voluntary process of extractive sector revenue disclosure and reconciliation between companies and governments. It has since evolved into a broad instrument seeking to improve transparency and accountability along the whole natural resource management value chain, including disclosure on corporate beneficiary ownership contracts, gender, environment, and commodity trading.fdd13c6a84b3

While national-level participation in the EITI is voluntary, the EITI Standard requires mandatory disclosure for all extractive companies, including state-owned national companies, as well as for the government, once the country has committed to the initiative. Compliant status requires implementation of strict standards of public disclosure, audit verification, and participation of civil society – with the international EITI Board deciding on members’ validation as compliant, and suspension or exclusion. In the first decade especially, implementation was mostly promoted through financial and reputational incentives, including at the initiative of development banks and international donors.ca301bf43542

EITI’s evolving objectives and approaches

The objectives and strategies of the EITI, and the disclosure campaign that led to its creation, have developed across three broad periods.

The first period, prior to the establishment of the EITI itself, ran from 1998 to 2002 and was aimed at using revenue disclosure to ‘name and shame’ government officials and extractive companies suspected of corrupt practices, and therefore bring some accountability and dissuade behaviours contributing to the ‘resource curse.’0e37b62970a7 During the first couple of years, the idea of disclosure mostly represented a threat to extractive companies and governments: exposure of corruption could lead to reputational damage and direct sanctions;d4b2706f1ae8 transparency of payments by companies could lead to infringements of confidentiality rules; and leaks about revenues earned by government could fuel public frustrations and civil unrest.

The EITI was conceived as a way to institutionalise disclosure, tame CSOs by enrolling them into a ‘constructive’ (if slow) process, and protect and even enhance the reputation of (mostly Western) extractive companies by demonstrating their goodwill and compliance to new anti-corruption standards. It was also seen by some international donors as a way to address the ‘resource curse’ and aid dependence within low-income resource-rich countries.9b78952842ec The choice of a voluntary instrument was not initially favoured by Global Witness, which – along with Oxfam and other early members of the Publish What You Pay coalition – had advocated for mandatory disclosure.436f6adc37de But in the face of resistance from home governments and stock exchange regulators, as well as the challenge of bringing about transparency for national extractive companies that were not publicly listed, the EITI appeared as a pragmatic and even promising option.

The second period, from 2003 to 2012, was mostly an attempt to institutionalise revenue disclosure for the purpose of building up government and corporate accountability, and reduce illicit financial flows from resource sectors.c4ca7bbcbbdc A crucial objective was to increase participation, including among the EITI Secretariat and supportive extractive companies, to the point where some highly controversial governments – such as that of Equatorial Guinea, under pressure from Exxon – were accepted into the scheme, before being rejected after failing to comply. Another important aspect was the consolidation of multi-stakeholder groups and the demonstration that such cross-stakeholder inclusiveness could function, and that the various stakeholders would sustain their participation, at both country and global levels. Both approaches largely worked and the rapid growth in the number of participating countries and continued support from governments, companies, and CSOs contributed to the EITI becoming more credible internationally.

The third period, from 2013 onwards, sees the EITI trying to enable tri-partite agreement on resource governance, help disclose and disseminate a large amount of information on extractive sectors, and ensure that this information translates into reforms that are effectively implemented. Drawing from a number of resources, such as the World Bank and Natural Resource Charter, both the EITI and the Revenue Watch Institute took on a ‘value chain approach’.024c7f38467d This has not specifically addressed the activities and outcomes related to disclosure of revenues, but has looked at the entire extractive industry value chain from the decision to extract to the allocation of revenues. The value-added in this approach is the focus on the different roles of the government, members of parliament, civil society, and media to build capacity and oversee the entire value-chain process.a563af036e02

Therefore, the EITI evolved from an anti-corruption tool to a resource-governance framework (see Annex 2). The ability to reach these objectives rests on a number of relatively similar assumptions: that information on extractive sectors can be collected and made publicly available; that this information can promote better informed public debates, and more effective resource policies and revenue management; and that governance in general will improve through the diffusion of transparency and accountability norms, including via the mandated participation of CSOs.20cf304359f3

EITI goals, uptake, and impacts

After about 17 years of operation, many researchers, practitioners, donors, and decision makers are asking to what extent the EITI has met its goals, why some countries are joining the initiative while others are not, and what have so far been its impacts.c3c296b15002 Overall, and as identified in Rustad et al.eb43b2dc5e06 (see also Annex 2), it has had three major sets of goals. These are institutional ones seeking to establish the initiative and transparency as a norm and creating multi-stakeholder groups as the basis of governance; operational goals seeking to implement the EITI Standard and boost public and civil society participation; and developmental ones seeking to bring concrete outcomes for implementing states and their populations when it comes to increasing the government share of natural resource revenues, improving the extractive sector revenue management, and enhancing development (Figure 1).

A meta-study of EITI assessments found that the EITI has been most successful in reaching its institutional goals, and fairly successful in reaching some of its operational goals, such as establishing the successive EITI Standards, but that it was difficult to conclude whether the EITI had had any impact on its development goals.11ff704af1ee

Figure 1: EITI goals identified through a broad review of EITI documents and literature on the EITI

| Institutional goals | Operational goals | Development goals |

| Goal I-1: Brand EITI globally and nationally | Goal O-1: Establish clear and credible EITI standards | Goal D-1: Increasing revenues that are returned to the society through reduced corruption |

| Goal I-2: Establish (EITI) transparency as a norm globally and nationally | Goal O-2: Increase state capacity to implement the EITI standard and report in timely and comprehensible manner | Goal D-2: Improve investment climate, increase aid flows, and promote fairer government share of revenues |

| Goal I-3: Increase EITI participation, compliance, and support from governments | Goal O-3: Increase public understanding, debate and influence of natural resource mangagement | Goal D-3: Promote good governance, sustainable development, and improved living standards |

| Goal I-4: Establish multi-stakeholder groups as the organizational basis and promote multi-stakeholder model of governance | Goal O-4: Ensure civil society's effective participation in multi-stakeholder groups |

Source: Rustad et al. 2017.

In terms of uptake, as of May 2020, the EITI counted 53 implementing countries,cbb6d898cfd0 including many resource-dependent, low-, and middle-income countries, and had helped disclose about 2.6 trillion US dollars of government revenues.6e3b0f5595d6 Yet, many resource-rich countries, including Angola and some of the most wealthy oil-producing countries, are still not part of the initiative and this raises questions about factors influencing participation, such as lower per capita resource wealth and higher donor dependence, rather than the need for reforms.81e66a1f26c7

Given the high number of corrupt (and often low- to middle-income) countries joining the EITI, David-Barrett and Okamura8ef268f032c4 suggest that the initiative serves as ‘reputational intermediary, whereby reformers can signal good intentions and international actors can reward achievement.’ The effects on corruption have also been questioned, with many pointing out that few, if any, bribes and embezzled funds have been recovered and jail sentences served. This is partially the result of EITI’s limits with regard to anti-corruption efforts, such as a lack of EITI mandate to investigate corruption, predictability in disclosure facilitating the identification of illicit financial flows that will avoid public reporting,f4e1edc449a0 ‘cosy’ relations among multi-stakeholder group (MSG) members, and limited engagement with other anti-corruption actors.3e036fc7920e More generally, the impact of the EITI on developmental goals has remained an open question. While difficult to assess, given the multi-causality of development processes, econometric studies have so far cast doubt on the pro-developmental effects of EITI implementation.60add9371195

EITI Theory of Change: Building a framework

To achieve the long-term goals of the EITI, a ToC is a useful tool to understand how various interventions will lead to change.e14e11ec1b12 By clearly identifying goals and interlinkages leading to effective change, a ToC could guide the EITI policies and practices, and at the same time allow for more rigorous evaluations. In 2011, the analyst company Scanteam conducted the first external and extensive evaluation of the EITI.f7baf61f7969 The report pointed out that the lack of a ToC has made it difficult to connect the ‘big picture indicators’ to the ‘big picture results,’ and thus to evaluate the success of the EITI. The lack of ToC is clearly stated in the report’s executive summary: ‘…there is not any solid theory of change behind some of the EITI aspirations’.dafa479599c0 Similarly, a report by the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) published the same year pointed out that one major design gap in the EITI was that it lacked a ToC to relate the initiative’s activities to the expected benefits, which made it difficult to evaluate impact.53472c1be6c7

As a response to the critique raised by these reports, the EITI Board decided, in June 2011, to establish a ‘Working Group on Theory of Change,’ which was to ‘develop a more rigorous and realistic results framework at global and national levels.9176b6e44ab2 At the board meeting a year later, the working group reported that they had ‘reviewed case studies from Indonesia, Nigeria and Tanzania. While there was evidence of implicit theories of change at country level, there was little evidence that EITI outputs such as EITI reports had led to change.’ Further, the working group pointed out the importance of ‘monitoring impact and developing a menu of indicators to better measure the impact at the national level.’92efc7d9f7cf However, there was no formal report published by the working group, and after the June 2012 EITI Board meeting there seems to be no mention of ToC nor the working group in the meeting minutes (See Annex 1).

This ambivalence towards a ToC – and a certain reluctance to set a ‘fixed’ framework to define and achieve change – was further underscored by the EITI International Secretariat’s most senior staff, Rich and Moberg,7989532dcd38 who concluded in their book that ‘there is limited benefit in a theory of change and little effort should be made to establish overarching goals.’ Further they saw a ToC as a linear process and not suitable for the outcomes of the EITI which are ‘unpredictable, intangible, non-attributable, and long term.’ Rather, Rich and Moberg12ad5eab623c propose a theory of collective governance (‘governance entrepreneurship’),2d7a39353927 where it is more important to establish a clear reason for meeting around the table, rather than grand common objectives. They argue that collective governance resembles more mediation than traditional development theory. And that, often in difficult mediation situations, it is more beneficial to focus on what one can agree upon, rather than continue to disagree on the larger issues. This would, in the long term, build trust and create space for further discussion and avoid a situation where a rigid ToC scares countries from joining the EITI.

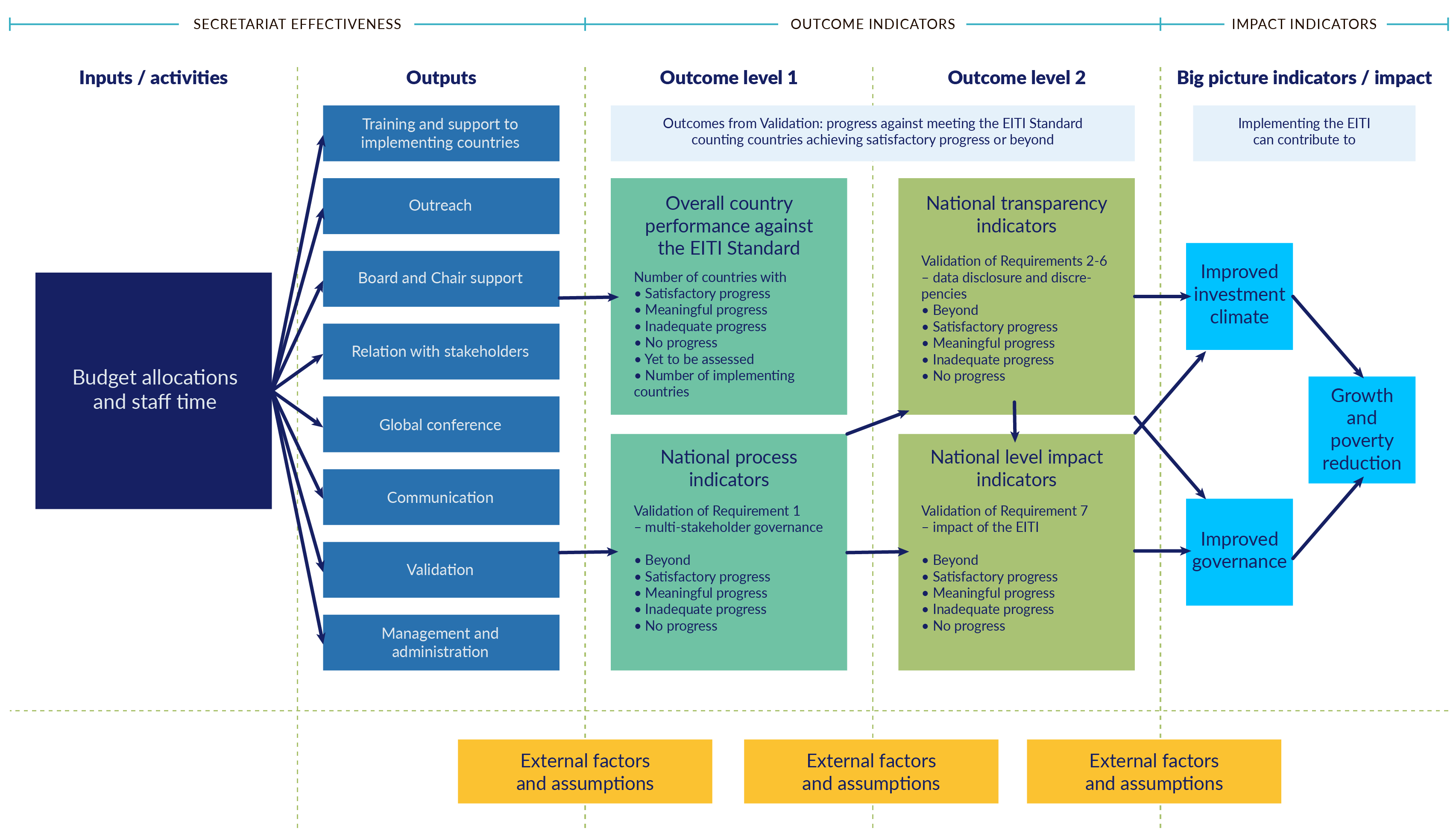

Since 2019, there has been pressure for the EITI to better show the impact that it has on the big picture development goals.619fc2d5aa61 As a result, the EITI International Secretariat Work Plan for 2020 presents the first formal EITI ToC (see Figure 2). The model is built around the EITI validation criteria, without disentangling what actually makes change happen.

According to this ToC, if a country scores satisfactory progress on their indicators, this ‘can contribute’ to improved investment climate and governance, and ultimately to growth and reduced poverty. Notably, the ToC does not specifically address interlinks leading to change, and nor does it specify how transparency itself influences the changes. Nonetheless, the EITI’s key performance indicators are embedded in this ToC and are the basis for measuring the effectiveness by the EITI’s international management (ie the International Secretariat and the EITI Board).09c903f9464f

Figure 2: Theory of Change developed by the EITI International Secretariat

Source: EITI International Secretariat 2020 Work Plan (EITI 2019a, 51).

Despite the hesitancy from the EITI, scholars and other organisations have made an effort to develop a ToC for the EITI. We present three different ToCs developed by external actors in order to better understand the EITI causal chain.70a0dafbe01d

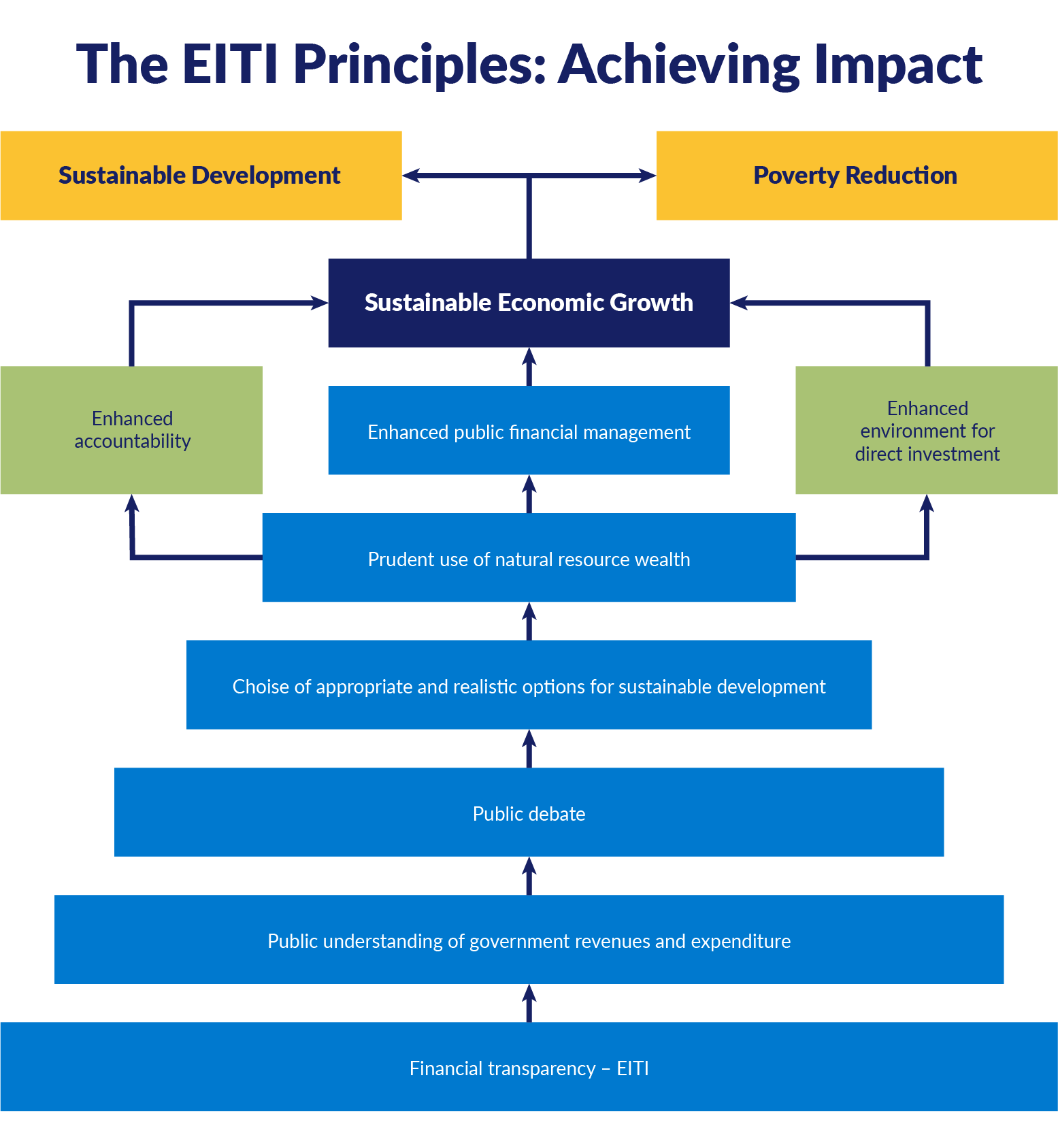

In 2014, the EITI Multi-Donor Trust Fund (MDTF) presented a ToC model in their Annual Report (see Figure 3).08b8453e6d53 As a donor organisation, the EITI MDTF needed a framework that would help it to define realistic expectations, target beneficiaries, and identify risks for the EITI, and understand how the EITI could initiate and support change. Its formulation of the ToC was a direct result of the two evaluation reports published in 2011,74b70bcc9328 and it draws on the work that was done by the EITI Working Group on Theory of Change.eab5fb6a61de

Figure 3: Theory of Change by the EITI Multi-Donor Trust Fund

Credit: Source: EITI MDTF (2014, 44).

The causal path in the MDTF model suggests that by bringing about (financial) transparency and fostering public understanding and debate, the EITI would help inform better choices over resource-development linkages and enhance accountability, public (financial) management, and the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) environment. This would lead to poverty alleviation and sustainable development. The MDTF stresses that this is not meant to be a one-size-fits-all model, but rather a tool designed to help countries situate the EITI indicators in relation to their specific national contexts.

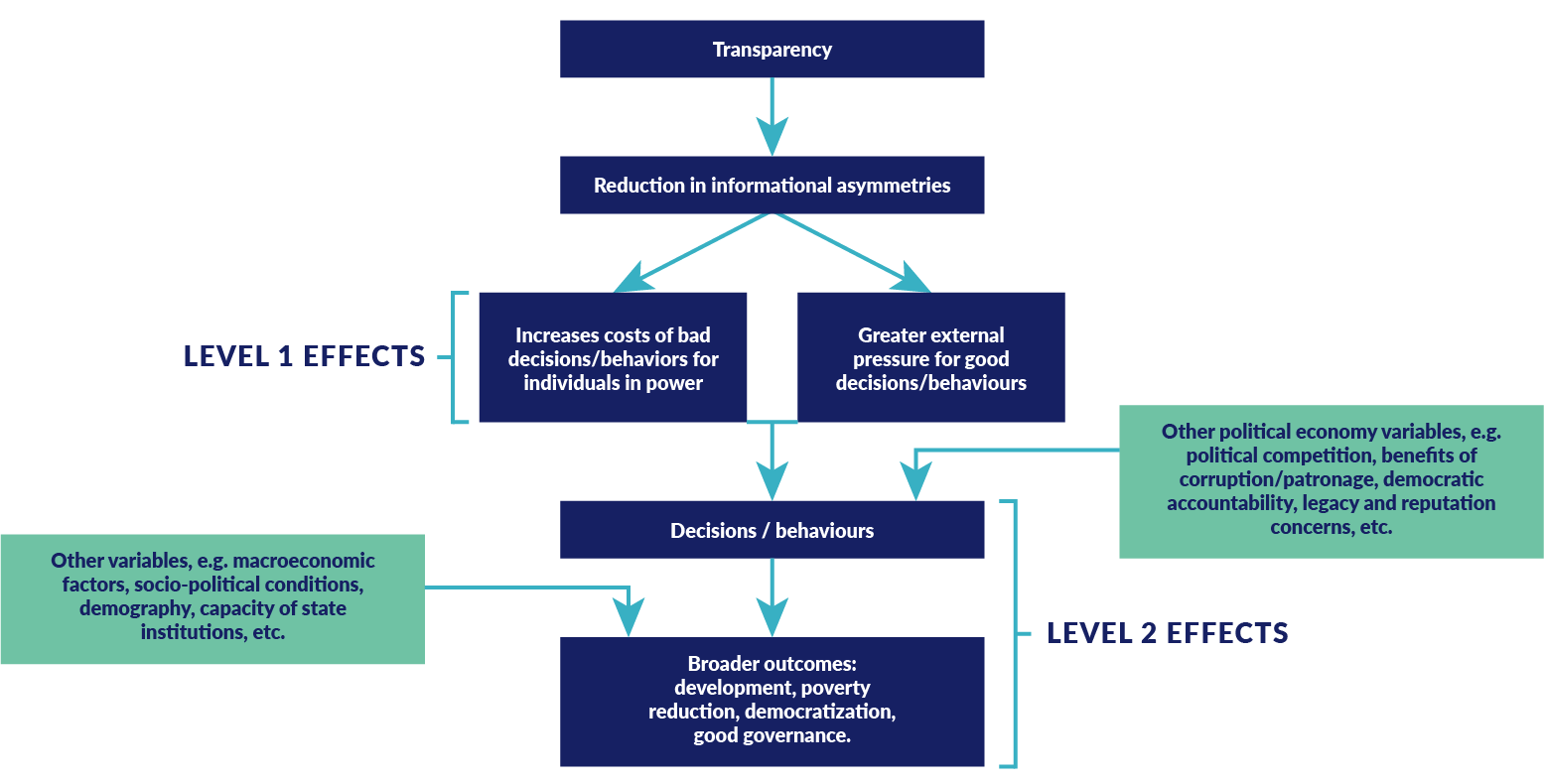

In their 2011 study about EITI effectiveness, Gillies and Heutyd44a3c0d3522 argue that transparency (defined as public disclosure of information in accessible formats) cannot directly affect the social and economic wellbeing, or the quality of governance. Instead, transparency can, through reduction in information asymmetries, affect the cost of making bad decisions for individuals in power and therefore lead to external pressure to improve decision-making and behaviour of those in power (Level I in Figure 4). These changes, together with other contextual factors, may then contribute to long-term developmental goals (Level II). This ToC model also accounts for the influence of other variables, both in terms of influencing decisions and behaviours, as well as with regard to the outcomes of these possible changes.

Compared to the MDTF model which stresses a pathway through public debate, the Gillies and Heuty model is broader. It does not explicitly point out what the mechanisms for change are, but rather indicates what transparency can influence; therefore, it leaves open what the actual interlinkages between transparency and long-term goals are. While this model is vaguer than the MDTF model, it is more open to context-specific understanding, and allows for more than one change mechanism.

Figure 4: Impact of transparency on the political economy of decision-making

Credit: Source: Gillies and Heuty (2011, 32).

A report by GIZaa81b56fa8b4 on the impact and effectiveness of the EITI focused specifically on the country-specific nature of a ToC. As part of their methodology, they conducted workshops with the country multi-stakeholder groups to develop country-specific ToCs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Mozambique. The results from the two countries were quite different. In the DRC the focus was on improved understanding of reports among civil society and better communication channels, resembling the MDTF model aimed at achieving change through public debate. Meanwhile, in Mozambique, the report pointed at more technical issues such as the national secretariat being too small, an absence of lack of high-level participants from the government and extractive industry in the national MSG, and a lack of mainstreaming of the EITI process.

The models presented above all suggest different pathways towards the desired goals of the EITI, and that these pathways can be country and time specific. Hence, by considering only one of the models, we might grasp only parts of what the Theory of Change for EITI could be.

Three Theories of Change for the EITI

Based on a review of EITI Standards and Principles, literature, and observations on and discussions around the initiative, we developed three different stylised ToC models for the EITI, taking their information disclosure approach as the starting point and increased development as the ultimate goal: ‘Name-and-Shame,’ ‘Public Debate,’ and ‘Technical Reforms’ (Figure 5). These models are simplified and seek to condense the transparency process into a minimum of easily understood steps. This categorisation and simplification makes it easier to think of key pivoting processes that can lead to change. It should be noted that these three ToCs are not mutually exclusive and can be combined or sequenced in order to improve a variety of developmental outcomes (eg stronger and more accessible social and health services; safe and well-paid employment; high-quality infrastructure; or a healthy environment). Furthermore, while we focus here on the principles of mechanisms that can lead to change, we note that implementation and enforcement play a crucial role in delivering change.

Figure 5: Three EITI Theory of Change models

Name-and-Shame Model (A)

Our first model, called ‘Name-and-Shame,’ proposes that by publishing data on revenues from the companies to the government – as well as other disclosure requirements such as licence allocation processes and transfers from state‑owned companies – it is possible to pinpoint which companies and government agencies have large discrepancies compared with each other when reporting revenue flows between the industry and the state and how large these flows are. The discrepancies, or unexpectedly small flows, can be investigated to expose possible tax evasion, corruption, or embezzlement. The focus is on leveraging transparency as an anti-corruption instrument to reduce revenue losses and improve the integrity of resource governance.

Model A was forcefully outlined in the Global Witness Reporta5ef6db1f297 ‘A crude awakening,’ which sought to denounce the complicity of large oil companies in Angola, like BP Amoco, ELF, Total, and Exxon, in the plundering of state assets. Global Witness called for higher levels of transparency from companies, convincing BP Amoco to commit to publish their payments to the Angolan government. This initial success was quickly dampened by threats from the Angolan government to cancel all of BP Amoco’s concessions in the country for breaching confidentiality agreements. This reaction led Global Witness to pursue the creation of an international instrument to enable such disclosures, leading to meetings with industry and regulators, the launch of the Publish What You Pay campaign, and the EITI.

The ‘Name-and-Shame’ model – and its complementary positive reputational effect for the companies’ and governments’ participation in the EITIfe1e4406c951 – can seem to be effective, at least in the short term and for incentivising some companies to disclose, as seen with the example of BP Amoco.e0fc2918cfc3 It follows on the idea that transparency can change the behaviour of companies or governments and bring accountability through disclosure, resonating with the ToC by Gillies and Heuty.86d33599ac54 Moreover, by helping to collect and disclose information – including on revenue flows, beneficial ownership, and contractual arrangements – the EITI can assist in triggering investigations into corrupt or abusive conduct. Even in countries with repressive governments that ‘feel no shame,’ disclosure can bring some longer-term form of accountability (see box below).

Conceptual critique and empirical evidence of Model A

While the ‘Name-and-Shame’ model can be effective, it does not find its roots in a broad civil society movement, the wider public, or a democratic process. Rather than seeking to diffuse transparency as a norm within society, it is used as a specific tool to instil fear of being ‘caught’ among companies and governments. Model A also supposes that investigation, divulgation, prosecution, and sanction will take place at the domestic or international level so that some form of accountability will result. As such, there is a risk that Model A will be ineffective for those who do not fear ‘shame’ or who can evade sanctions given existing power relations, or who cannot be voted out of office.

There are many examples of raw power abuse in EITI implementing countries where domestic constituents know what has been happening with extractive sector revenues, but because of power configurations are unable to do anything about this. Further, using fear and threats to promote the cause might harm the relationship between the stakeholders in the MSG, as the Angolan case indicates. This can lead to a difficult environment for dialogue and cooperation and undermine the purpose of the MSG. Finally, tax-evasion, corruption, and embezzlement may not be the main issues preventing extractive revenues from having positive impacts on development, which makes an EITI process that follows this model quite irrelevant.

Despite these challenges and limitations, Model A holds some value, even in the most repressive contexts. The methodical documentation of abuses for future domestic or foreign legal proceedings can bring some accountability results, even if there is little evidence of deterrence effects in the short term. Sanctions may not be immediate and may only come after a regime transition. But the idea that there is someone watching and documenting some of the abuses is still a powerful one.

Public Debate Model (B)

The second model is based on what is probably the most common perception of what the EITI ToC is: leveraging transparency as a public debate process to improve resource governance.47329f3dd731 For example, the ToC outlined in the EITI MDTF 2014 report underscores the importance of public understanding and public debate as being essential for improvement of the natural resource government. This is also reflected in the EITI Principle Number 4: ‘We recognise that a public understanding of government revenues and expenditure over time could help public debate and inform choice of appropriate and realistic options for sustainable development’.ab74b90e72e6

The Public Debate ToC is very much in line with democratic values and the EITI’s ideal of including the public and civil society in the transparency process. This approach also resonates with what Rich and Moberg60c0a15bcbd4 refer to as collective governance, in which all three stakeholders – government, companies, and in particular civil society – together with the public have a key role in ensuring accountability through mobilisation to press the state to improve its natural resource (revenue) governance. It is crucial to note, however, that the lack of freedom of expression for CSOs in repressive political regimes can drastically undermine the viability of Model B (see below). This issue led, for example, to Niger and Azerbaijan’s suspension and then withdrawal from the initiative. Insufficient engagement with CSOs has also occurred in more ‘mature’ democracies, such as in the case of the UK’s EITI MSG – which saw the EITI Board noting ‘that civil society’s engagement had been insufficient in the period reviewed by Validation’ and encouraging the UK government ‘to ensure that challenges in constituency coordination are avoided in future’.dc49a5a3c835 More generally, the EITI’s CSO protocol has been criticised on numerous occasions for not being protective enough, while numerous cases of threats against CSOs have been reported by Global Witness and PWYP.1edebfeba23f

Conceptual critique and empirical evidence of Model B

In their meta-study, Rustad et al (2017) report that very few studies find evidence of the EITI being able to promote accountability through public debate. The main challenge with this model is the assumption that the civil society will be able to use the increased transparency to create awareness in the public and then foster change as a result of ensuing debates.

To make this happen, a strong coalition with key civil society actors and gate-keepers (such as the chairs of relevant Parliamentary committees or the editors of independent media) is important. However, civil society is very broad and its ‘organisations’ often have divergent or often conflicting interests and the general public’s interest is often not in national-level issues, but rather local-level ones. Neither is providing information to the public useful unless they are empowered and equipped to understand and use it to create public debate. This requires specific efforts to address lack of capacity to use data, complexity of information, and issues of access to broad constituencies – including within the often poorly represented remote regions where extraction is taking place.

Analyses carried out by CSOs (for example in Indonesia or the Philippines) and more systematically by organisations such as OpenOil, and of course the numerous analyses published by EITI and Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), have the potential to make a difference, at least in terms of awareness, even in the many countries where government repression hinders public debate. In some cases, mass participation may not be possible, or needed, as intermediaries can more efficiently perform the role of watchdog on behalf of the public.

Technical Reforms Model (C)

The Technical Reforms modelfocuses on leveraging transparency as an informational tool as well as a legal and bureaucratic process to improve resource governance through improved regulations, institutions, and processes. This includes broad legal reforms often inspired by the very principles of EITI compliance (eg mandatory disclosure legislation), and the outcomes of public debates associated with Model B (eg new petroleum and mining codes integrating transparency and reporting requirements; disclosure of beneficial ownership). But it also includes narrower regulatory adjustments within existing administrative and corporate structures to close gaps or improve efficiency in data management as a result of EITI reports highlighting weak processes that had not received much scrutiny before.2bf6e6ea6d49 Such changes may come from demands by civil society participants, but also from civil servants who are either better (or newly) informed about poor practices or more directly ‘named and shamed’ by these findings (hence a link with Model A).

In this model, the EITI national reporting has a dual role. First it increases transparency through publishing revenue flows, and second, but just as important for changes, it can reveal shortcomings in governments’ management and reporting systems. Based on the shortcomings that the EITI reporting exposes, the national EITI is expected to provide recommendations for improvement, and therefore contribute to governments’ policy reforms. According to the 2016 EITI report ‘From reports to reform’: ‘In many countries, the most important contribution of the EITI has come about because governments have decided to act on recommendations that have emerged from EITI reporting’.bb8dc968c482

For example, the Nigerian EITI (NEITI) pointed out issues with lack of monitoring and management of oil transported via pipelines. This was followed up with the government and the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) and resulted in implementation of a digital measuring system, pointing to the need of incentives to carry out reforms – whether as a result of incentives and/or sanctions. Overall, Model C is likely to be sensitive to the quality and capacity of state institutions, with higher quality and capacity resulting in faster and more impactful responses. As such, an efficient and relatively independent bureaucracy will deliver technical reforms, even in the absence of a strong political commitment for reforms.

Conceptual critique and empirical evidence of Model C

The advantage with this model is that it can be more efficient and less time-consuming than the public debate channel, and can have more lasting effects than ad hoc anti-corruption efforts. The disadvantage is that it includes fewer stakeholders and may thus be biased towards certain interests. Similarly, the process might not get a strong foundation in the public and civil society, hence there might be less trust in it. Further, the recommendations based on the EITI national reports are not mandatory, so there is no guarantee that they will be implemented.

For example, in Peru, the 2008–2010 EITI report recommended that the government should improve routines for licensing data. However, as of 2016, the government and the national MSG had not yet considered this recommendation (EITI 2016, 6). Out of ten African countries examined, none had fully implemented the recommendations made in the EITI report (Lemaître 2019), though some important reforms were conducted that, for example, helped strengthen civil society and inform IMF programmes.

Assessing EITI goals and potential ToC models

We conducted a survey among participants at the 2019 EITI Global Conference, held in June 2019 in Paris, using an online questionnaire. An enumerator introduced the survey to the respondent and handed over a tablet and a chart for the three ToC models. The respondent returned the tablet to the enumerator after completing the survey, which sought to map various EITI stakeholders’ thoughts on what they perceived to be key objectives for EITI and their experience with a Theory of Change. Also they were asked to indicate what they saw as the main steps to achieve change in the context of EITI, and which of the stylistic models they felt was the most fitting for the EITI (see Figure 5). The questions were mainly closed-ended.

In total, 59 participants took part in the survey. The respondents worked in 38 different countries: 15 in Africa; 12 in Asia; 7 in Western countries (including Australia); and 4 in South America. Forty of the respondents declared that they represented a particular EITI country. Most of them worked for or represented the national EITIs, NGOs and CSOs, government agencies, and extractive companies. Sixteen respondents declared that they did not represent a specific EITI country,0e2a2ed466ae often working for the EITI International Secretariat, extractive companies, institutional investors, academia, or media. The length of the respondents’ engagement with the EITI varied from one year to over 16 years, with two respondents indicating that they had engaged with the EITI since 2003 or earlier. A little over 40% of the respondents had been engaged with it since at least 2010, and around 75% since at least 2015.

We conducted 24 semi-structured interviews in three countries – Colombia (6), Ghana (13), the United Kingdom (5) – and one interview with the Norwegian Agency for Development Corporation (Norad), responsible for EITI in Norway, in order to gain a deeper understanding of national-level perspectives across a range of stakeholders (see Annex 3 for a list of interviewees). Interviews were carried out in person in Ghana and the UK, and over Skype with respondents in Colombia and Norway, between December 2019 and March 2020.

The selection of these countries reflects regional criteria (noting the absence of an Asian country), status at the time of the research (‘satisfactory progress’ for Colombia and ‘meaningful progress’ for Ghana and the UK), research team languages (English and Spanish), previous contacts within countries, and logistical constraints at the time of the research (including restricted options on travelling). Given these, and the small size of the sample, our results cannot be considered representative of the vast array of country-level experiences with the EITI. The semi-open interviews followed a common template for all four countries (see Annex 4 for the interview script). The interviews were transcribed and then analysed by all three authors in order to identify key observations on the EITI processes and factors of effectiveness, fit between the three models, the situation in the country as seen by individual survey respondents and interview informants (hereafter, interviewees), and general recommendations.

In addition to the material collected specifically for this particular study, the authors’ engagement with the EITI dates back to the late 1990s and the pre-EITI discussions on transparency strategies for extractive industries. Since then, the authors have participated in several EITI Global Conferences (2009, 2011, 2016) where they have observed the discussions and presentations, conducted formal and informal interviews, and engaged in discussions with other participants across all stakeholder groups, including the representatives of the EITI International Secretariat. Furthermore, the authors have engaged in dedicated interviews and discussions on other occasions in Ghana, Indonesia, Norway, and Sierra Leone that also inform this discussion.

What are the EITI goals?

The EITI has many goals,051887afa08c but when asked about this as an open question5c72770c7450 our respondents overwhelmingly stated that the principal goal for the EITI was to increase transparency. Improved accountability/better resource sector governance was evoked by several participants, and developmental objectives were mentioned by three respondents. Only a few stated goals like increasing FDIs (two respondents), promoting multi-stakeholder engagement (two), curtailing corruption (one), or improving the country’s international reputation (one). Notably, no one mentioned public understanding or public engagement as a goal, except for one who answered ‘change minds,’ without specifying whose minds should be changed.

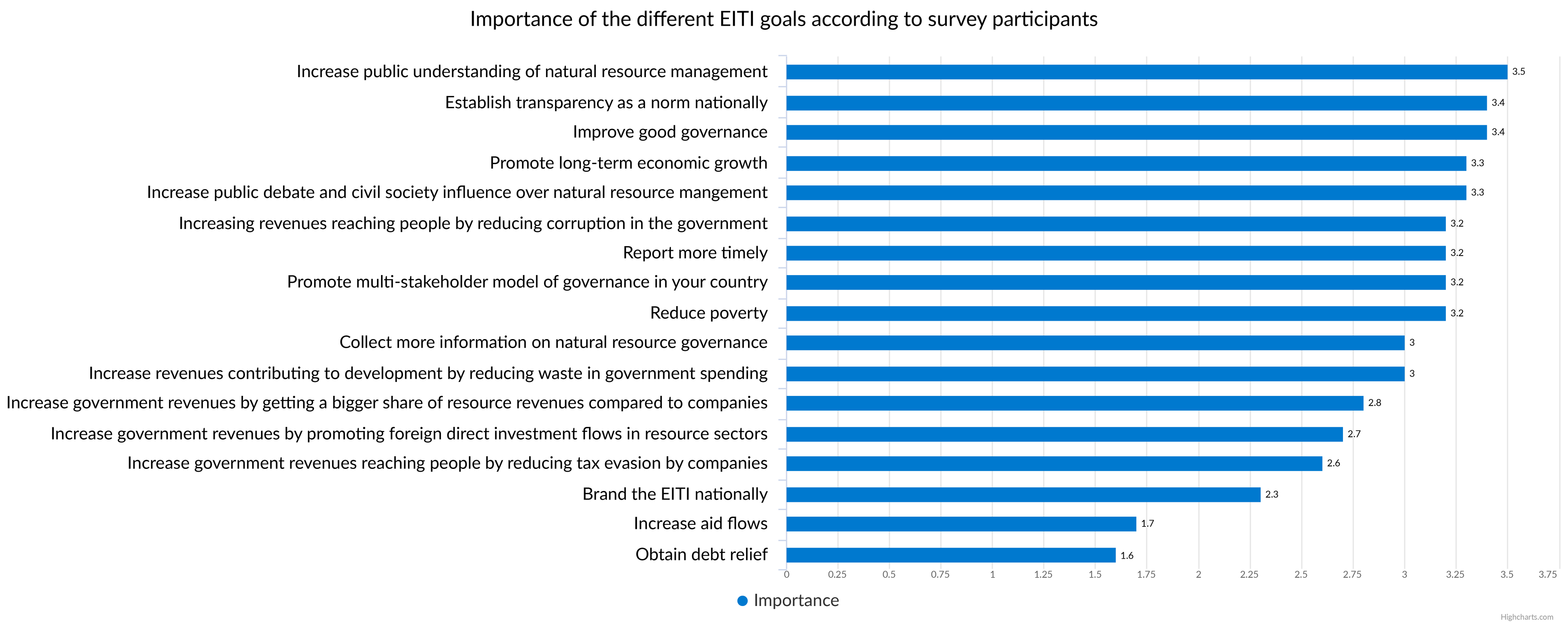

A slightly different, and more nuanced picture, emerged when the respondents were asked to rate specific EITI goals, based on the Rustad et al.f7658f3fbc6e categories (see Figure 1), on the scale from ‘Not important’ (0) to ‘Very important’ (4). Although the respondents rated ‘establishing transparency as a norm nationally’ together with improving good governance as very important goals, objectives related to the ‘public’ were also deemed to be highly important, notably those of increasing public understanding of natural resource management and widening public debate and civil society influence over natural resource management (Figure 6). More long-term goals were also regarded as important, among them promotion of long-term economic growth and reduction of poverty.

Among our survey participants, increased aid flows and obtaining debt relief were the least important goals. We also note that, in general, our respondents rated specific ways the EITI could potentially increase government revenues (ie increased FDI in the extractive sector, reducing tax evasion by companies, and increasing government share of resource revenues) as relatively less important. Among those who indicated that they represented a particular EITI country, obtaining FDIwas a rather important goal (average score of 3.1), while the other respondents rated this only as a moderately important goal (2.1). There is also some evidence that attracting FDI was more important for the Asian respondents (average score of 3.4).

According to our interviewees, the reasons for joining the EITI varied greatly between the countries. For the UK and Norway, joining the EITI was mostly a symbolic affair in the sense that the countries felt that they already were doing many of the things that the EITI demands, but that it was necessary to show that the EITI is not just an initiative for resource-rich developing countries.

Figure 6: Importance of the different EITI goals according to survey participants

Scale

0 – Not important

1 – Slightly important

2 – Moderately important

3 – Important

4 – Very important

Reputational aspects were also mentioned by several Ghanaian interviewees, who thought that the government of Ghana prefers to present itself globally as a country that is making serious efforts to promote good governance. At the same time, most Ghanaian interviewees felt that adoption of the EITI was the result of a genuine interest within the government to address the negative externalities caused by mining and the lack of development in the country despite over a hundred years of extensive gold mining. Further, the informants noted that the underlying motivation for the government was to bring the opaque extractive sector under a firmer state control and increase the government share of extractive revenues.

In Ghana and Colombia, prior to the establishment of the EITI, the governments had already started processes to more firmly manage the extractive sectors and, according to our interviewees, the EITI was useful in that work. By signing up, the governments could show that they took changing the status quo seriously, answered the call by civil society for increased transparency and accountability, and established a trusted, third-party platform to provide information on the extractive sector revenues. Thus, the EITI was adopted because the governments saw it as a vehicle that would support their objectives for the sector but also, and sometimes more importantly, bring reputational benefits nationally and internationally (eg the Colombian government was keen to use the EITI to advance its OECD candidacy).

Among civil society in Ghana and Colombia, the concerns over the extractive industry were not limited to revenues, but were more about the social and environmental externalities that the sector caused. Most civil society representatives stated that they initially saw the EITI as an opportunity to promote dialogue with the extractive industries companies and the government to address concerns related to the negative externalities caused by the sector. Those representatives also stated that they had hoped the EITI would help in understanding how much revenue was transferred to local governments and communities, get information about the licensing processes, and assist in addressing the local tensions around extractive projects.

A ToC for the EITI?

Most of our survey respondents (60%) agreed or strongly agreed that it would be useful to have a ToC for the EITI, suggesting a clear demand for it among Global Conference participants. Only one respondent disagreed with the statement, while 20% of the respondents remained neutral and 14% answered that they did not know. About half of respondents who represented specific countries indicated that their national EITI had formulated a ToC or similar, or was in a process of doing so, and among these, two-thirds had personally been involved in the process. Our interviewees also saw a ToC to be beneficial, and at least in Ghana and Colombia there had been discussions about how to link the EITI information disclosure to changes in natural resource governance and broader societal development.

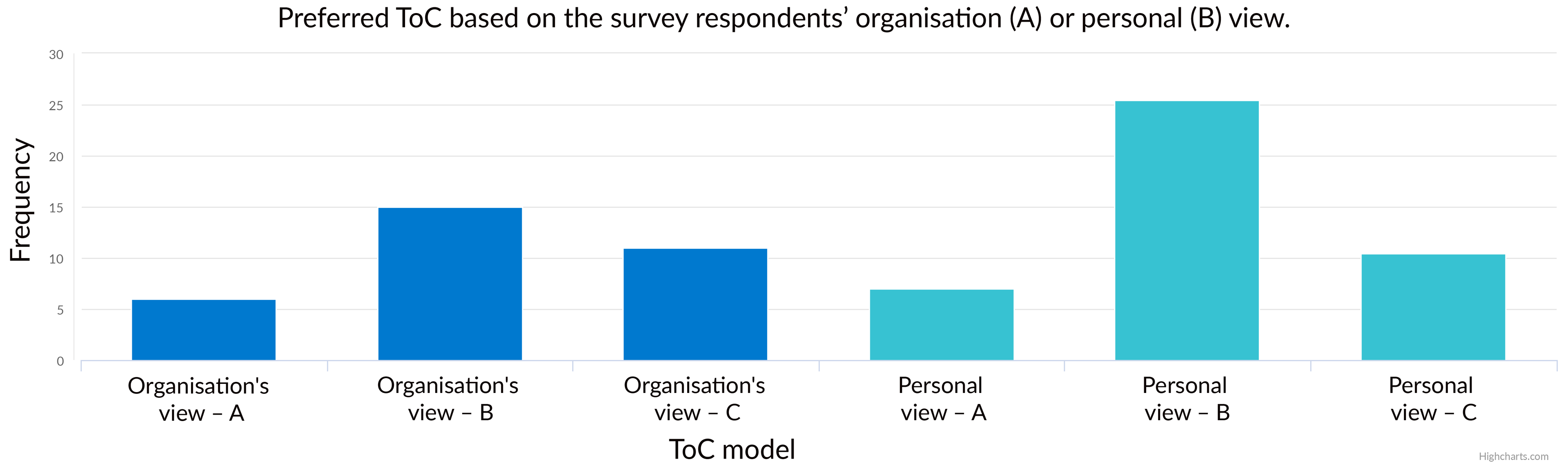

When presented with the three stylised ToC models for how the EITI could potentially lead to improved developmental outcomes, our survey respondents chose the Public Debate ToC (Model B) as the one that best represented their organisation’s view and that they personally thought to be the best model for the EITI (Figure 7). Technical Reforms ToC (Model C) was the second most popular among our respondents and their organisations.

Figure 7: Preferred ToC based on the survey respondents’ organisation (A) or personal (B) view.

Note: Many of the respondents did not know which model was most in line with their organisation’s thinking.

In the survey, the respondents had to choose one of the models as their preferred option, while in the interviews a more nuanced picture emerged (for a summary, see Table 1). Model A (Name-and-Shame) was often seen as an initial motivator of the EITI, especially among civil society. Model B (Public Debate) was recognised as the basic principle and approach of the EITI. Model C (Technical Reforms) was identified as the most pragmatic and effective way through which the EITI had so far made a difference. Many interviewees thought at least two or all three of the models fitted their country, especially in Ghana where most interviewees deemed all three models relevant. Moreover, several interviewees pointed out that the models work in parallel, often being complementary and feeding into each other. Although the interviews revealed that the country-specific fit varied between our three case countries, there were also some common perceptions.

Table 1: Summary of Model fit by the case country

| Models / Countries |

A – Name- and-Shame |

B – Public Debate |

C – Technical Reforms |

|

Colombia |

Least relevant model as other anti-corruption processes are in place and corruption issues are mostly associated with subnational authorities and, so far, poorly covered by the EITI |

Most relevant model as EITI reports inform some public debates, but very limited due to lack of dissemination and limited interest |

Second most relevant model as the EITI clarified and helped to correct bureaucratic processes, and informed reforms |

|

Ghana |

Relevant in the sense that it forces the companies to pay their dues (taxes, royalties, surface rentals etc.) and to comply with the information disclosure requirements |

Relevant to the extent that the EITI is making a lot of information available to the general public. Seen as rather irrelevant currently as the link from the disclosed information to accountability is missing. |

Relevant as the EITI has improved revenue collection and informed polices, regulations, and legislation concerning the extractive sector |

|

United Kingdom |

Not relevant |

Could be relevant but of limited impact as the general public is not interested in the issue |

Relevant. EITI was used to push some reforms through faster in the early days, such as project reporting. |

Model A was generally seen by interviewees as initially relevant and motivating, especially on the part of CSOs which initially pushed for the EITI adoption. There was a sense that ‘naming and shaming’ had helped to secure the participation of the companies, forcing them to ‘open their books’ or have their names published in the annual EITI report; limit intentional and non-intentional tax evasion; and point at underperforming government agencies not being able to claim companies to pay their taxes and other payments.

None of the case countries had seen the EITI directly expose clear-cut cases of corruption, and exposing corruption was not seen as a key responsibility of the EITI. Rather, the EITI was perceived as having a supporting role in the upholding and enforcement of anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws through the provision of third-party audited data. There was a perception among many Colombian and Ghanaian interviewees that the EITI had helped, rather than undermined, the companies to improve their public image through disclosing their contributions to the government, notably by giving them a credible platform to communicate.

Model B was seen as the foundational principle of the EITI, one that constitutes the core of the approach. Yet few interviewees asserted that the dissemination of information and its contributions to public debates had contributed significantly to improving the governance of extractive sectors and its revenues. Although the EITI was praised for having made information public, the absence of feedback mechanisms from the information disclosure to increased accountability specific to this approach was seen as making the EITI increasingly obsolete.

Echoing the views of our interviewees and despite choosing Model B as their preferred option, only two of the survey respondents, when asked in an open question what they saw as the crucial steps to achieve the EITI’s main goal, evoked the ‘public’ explicitly. A few more mentioned civil society involvement, or open discussion or communication. When asked in more detail about how effective the public debate had been in the respondent’s country (for those representing a specific country) or in general in countries implementing the EITI Standard (for the other respondents), the respondents found that public debates had only to some extent been successful in empowering civil society and citizens and improving resource governance, and only to a small extent in increasing government’s share of resource revenues.47dea2901a15

According to the interviewees, Model C was often seen as the main process through which change had been observed so far. The recommendations from the auditors and steering committees in Ghana and Colombia had helped in improving the revenue accounting; exposed instances in which lack of capacity and inadequate fiscal regulations had hampered revenue collection; and influenced legislation, regulations, and policies concerning the sector. In Ghana, for example, EITI implementation influenced the Petroleum Revenue Management Act 815 (from 2011) in which many of the transparency and accountability provisions are a result of lessons learned from the implementation of the EITI. It was, however, noted by several interviewees that EITI does not directly increase accountability through Model C as there are no mechanisms for forcing the states to adhere to the recommendations.31ddce62f4ac

In general, there seems to be a mismatch between the ‘preferred’ mode of impact, or what it ought to be ideally (ie the Public Debate ToC), and current reality (ie the Technical Reforms ToC). This was aptly shown in our interviews in Ghana, where nearly all interviewees stated that Model B is important, relevant, and even the foundational one for Ghana. Few came with solid accounts as to how it had (so far) led to change, while most were able to state several specific examples of how the EITI had led to reforms through other processes (eg technocratic reforms on information flows). Overall, this points to the value of tailoring, but also in some cases integrating these three ToCs, so that they allow for different logics to work in different stages of the process, and enable different logics to work for different types of stakeholder.

Development of the EITI ToC: Key considerations

What to build on

Credible information

The EITI was seen by many interviewees as providing highly factual and credible information that is respected by the different parties. This, in turn, was understood by interviewees as allowing for more meaningful debates and possibly more effective reforms (Model B). The country representatives in our survey also stated that the EITI in their countries had been successful in collecting and making information public and in increasing transparency in the extractive sector.981cb6f401b1

A fundamental message here is that the EITI should continue to be a reliable disclosure and verification mechanism. In this regard, we note that some interviewees pointed to the mainstreaming of disclosure processes within other government bureaucratic procedures as giving an impression of duplication that could lead to the closure of EITI-specific institutions such as the national secretariat, as it may appear redundant. Several interviewees warned against shutting down the EITI process, arguing that unless a similar approach involving MSGs and independent auditing can be secured, this would in some cases reduce the credibility of disclosed information.

Constructive dialogue

The EITI has enabled constructive discussions between governments, companies, and civil society representatives, which is especially important for ToC Models B and C. As expressed by a Ghanaian interviewee, the EITI ‘has really, really helped to pull us all together, from different stakeholders, different positions, … [and] come to put Ghana at the center of our conversations.’ The EITI has also been a learning tool and process for stakeholders, including for government officials and civil society to learn about the industry, and vice versa.

Therefore, the multi-stakeholder approach has improved dialogue and trust among the stakeholders, even when they were very sceptical at the beginning of the EITI implementation process, and enabled them to share information and identify key issues needing attention. Several interviewees, however, were concerned that ‘true dialogue [had] progressively died down and the EITI [had] became more of a bureaucratic exercise’058ba21de5bf and that the dialogue needed to focus on issues which are in the core of the sector, but not necessary related to national revenue management (eg the externalities that the industry is causing in the local communities).

Reforms

In Ghana, the EITI has contributed to a number of legislative policy and institutional reforms, and this was seen by most of our interviewees as the main channel through which the initiative is currently bringing about change in their country. With regard to the technical reforms, the survey participants saw the EITI Standard as the most important source for technical reforms, motivated by the need to pass the EITI validation. There thus seems to be a foundation for ToC Model C.

A key point here is that the EITI has, at least in some countries, resulted in changes in extractive sector management. At the same time, it is noted that the EITI Standard does not include mechanisms that would require the participating countries to discuss and implement reforms beyond implementing the Standard.

What to improve

Outreach and the use of information by the public

In the UK, both the CSOs and EITI national secretariat voiced concerns that the public was not interested in issues related to extractive sector revenues. Even if the information was out there, nobody really cared enough to engage in a public debate. The UK interviewees did not think that the public was interested in the EITI or natural resource management; in contrast, the Ghanaian interviewees were optimistic about the public being increasingly interested in extractive sector management.

Survey respondents did not identify public interest as a limiting aspect for the public debate or the success of the EITI in their countries, but rather saw the challenges to be the information disseminated by the EITI not being useful to the public and the low capacity among the public to analyse and use that information. As stated by a Ghanaian civil society representative:

What do you expect citizens to do with the information? Recently, I saw a typical oil contract which had been disclosed on the Petroleum Commission websites because the EITI requires that we disclose contracts. But ordinary people do not understand contracts. So what can they do with it? … Now recently, I looked at the draft beneficial ownership register of Ghana. It’s so complicated. I don’t understand shareholding transactions, debentures, all that. You need a dictionary. So how about the ordinary people? … One of the ways in which we are able to address the abuses in mining and oil sector is to resort to the court. So courtroom advocacy, litigation, public interest litigation. But here’s the case, I may feel aggrieved … I want to go to court and get the court to reverse [a] decision, but I don’t have the money. So, as a citizen, I can only grieve over it, and that’s it.

The survey participants rated the EITI in their countries as being ‘moderately’ to ‘very’ successful in bringing greater transparency to the extractive sector and making information publicly available. Yet, according to our interviews – at least in Ghana and even more in Colombia – the dissemination of information among the general public was either limited or seen as generating relatively little return. The interviewees noted that the dissemination strategies used in Ghana did not necessarily reach most citizens, as the EITI dissemination workshops ‘only reach a couple of hundreds of people in a place at a go. To reach almost everybody you would have to go into the media, not just any media but a media that reaches out to the ordinary persons’ (a Ghanaian interviewee).805770b8d4f7

In Ghana, it seems that dissemination has been an end in itself, with relatively little feedback from the population. This presents the outreach as a reassurance mechanism that can help assuage concerns of misappropriation and misspending. At worse, the current information dissemination was seen by some Ghanaian interviewees as a social strife and grievances prevention mechanism, making promises of revenues to develop communities, but with little effective impact on the ground.

A key message here is to carefully consider: who the end users of the disseminated information are; how to reach them; and by which means to provide the information. Attention must also be given to the types of tools that citizens can use in order to participate in the debate(s) and voice their concerns and demands to their leaders regarding extractive sector and resource revenue management. An eventual EITI ToC must include these mechanisms and specify how they are provided for. A ToC should also consider the complex interplay between information dissemination processes, public awareness, and decision-making by companies and governments. This is especially so if it is based on Model B. For example, whereas media reporting is no guarantee of public awareness it may nonetheless affect the calculations of company managers, investors, politicians, and bureaucrats.360d9f81fbd2

Civil society strength

In the narratives of transparency, civil society is often seen as having a pivotal role in accessing, interpreting, and disseminating information to the public as well as functioning as a watchdog towards the state.843076515aba This requires a civil society that is strong, unified, and well resourced. However, civil society was often seen by our interviewees as weak and with limited capacity, as it consists of a few dedicated persons and organisations with limited financial resources and often a high turnover among staff (including some moving to the private or public sector once trained). Another concern, especially in Ghana, was that CSOs may have been to some extent co-opted by extractive interests so that the outcomes, including public debates, focused more on raising revenues than addressing some of the broader socio-environmental challenges of extractive industries.

So, civil society needs to have access to information but also be capable of interpreting and mobilising it politically – through social movements or the political system – in order to effect change. This is the not only the case in Model B, but also in Model A. Especially when anti-corruption mechanisms and other accountability instruments are captured or ineffective, and demand broader changes than Model C would suggest (ie a fine-tuning of existing processes and institutions).

Interest and uptake by relevant state institutions

A general observation among many interviewees is that the EITI is ineffective when its findings are not considered by the relevant institutions, such as revenue agencies, anti-corruption agencies, and prosecutors. This can be damaging to ToC Model B, but also – most importantly – to Model C given that this model essentially relies on the responsiveness of other agencies to EITI policy inputs and recommendations.

The main implication is that the EITI would benefit from greater outreach within government, for example through the presence of representatives from organisations on the national EITI MSG and board (if there is one), clearer communication channels and communication products between the EITI and relevant agencies, and high-level inter-agency coordination.

Firmer integration of subnational issues

Several interviewees, in both Colombia and Ghana, noted that a more profound inclusion of subnational level extraction is a major area for improvement for the EITI. Efforts to account for natural revenue flows at the subnational level have so far remained at the pilot level (Colombia) with Ghana’s EITI (GHEITI) having integrated this more firmly in its EITI reporting. Several of the Colombian interviewees expressed that they felt that EITI was less relevant for them as it did not include information on the subnational level, for example. This is because much of the corruption in Colombia is related to distribution of revenues locally and not at the national level.

A fuller integration of the subnational level in the EITI would enable governments to show in more detail where the revenues come from, what they are used for, and where. It would also engage citizens on issues that perhaps are ‘closer’ to them and may even have a direct, personally felt impact. This has potential to improve the public debates at both the local and national level, and include other sections of the public than those in the capitals, or with more education or otherwise a better position in the society.

From information disclosure to accountability

The general sense among our interviewees in Ghana and Colombia was that although the EITI had been successful in producing and publishing high-quality data on the extractive sector, especially on revenues, it had not had an impact on accountability and was thus rapidly losing relevance. According to the interviewees, the EITI does not equip citizens with tools to demand accountability, does not have power to prosecute, and does not outline mechanisms that would ensure accountability – the result being that governments are still able to spend revenues as they see fit. Further, there was a feeling that as information disclosure becomes mainstreamed through general government institutions, there is a need for the EITI to provide added value and progress for it not to become obsolete in the implementing countries that have mainstreamed information disclosure (but not yet demonstrated positive impacts in terms of developmental outcomes).

At least in Ghana, there were several indications of increasing frustration among civil society representatives who felt that ‘we have done everything in the book that we are supposed to do, and yet, we haven’t been able to make that critical transition from disclosures to accountability’ (a Ghanaian interviewee). They continued: ‘We should be asking ourselves, “What next?” … In that process, we are now focusing our attention on the missing link … [that] needs to be identified and addressed. Because EITI international doesn’t actually have that.’