Blog

Threats to independent journalism post-Covid-19: what are the impacts for anti-corruption efforts?

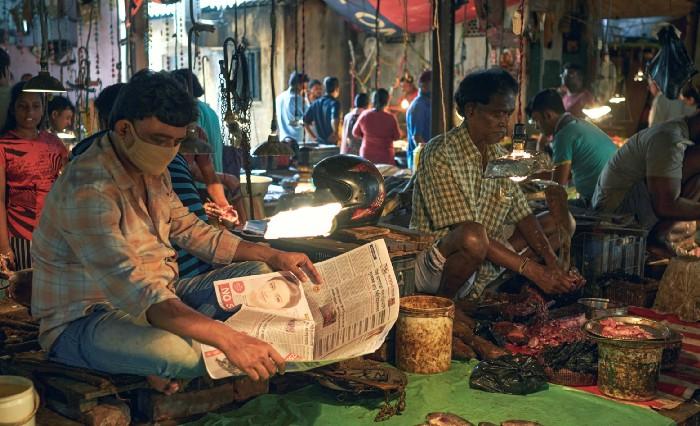

We would not know as much about corruption today, without the courageous efforts of individuals to expose cases of gross abuse of power. Think about the big stories that have hit the world’s media over the last few years: the Panama or Paradise papers, for example. Think also about the risks involved: the fate of anti-corruption journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia is bone chilling. Often it is investigative journalists that are on the frontline. But for how much longer?

Threats to accountability and press freedom

The current pandemic is having a profound effect on governance the world over. In many parts of the world, simple things like meeting friends is no longer possible. This makes more complex engagement – such as popular protests or social accountability – even more difficult. The opportunities for digital engagement are discussed here. But another piece of the puzzle for wider mobilisation against corruption is the role of journalists. However, their role is limited if independent media outlets willing to publish their reports are constrained.

As governments implement lockdowns, social distancing, and quarantine measures, they are at the same time drafting and enacting emergency laws with disturbing speed. While many of these laws may be introduced with public safety in mind, several place serious restrictions on press freedom and other fundamental rights. A tracker launched by Reporters Without Borders follows the latest restrictions placed on journalists and media outlets. It makes for worrying reading. The question remains, will these laws be removed as quickly as they were introduced once the crisis is over?

How free is the media anyway?

Freedom of the press was limited even before the pandemic. For example, last year The Media Reform Coalition published a report that showed in the UK, 83% of newspapers were owned by just three companies. Unfortunately, this trend is neither limited to the UK nor is it new. Over the last decade or more, we have witnessed increasing concentration of media ownership. This is shown in this report prepared for the European Commission covering EU member states. For a study of the global situation, and Latin America in particular, see this Unesco report.

Civil society organisations have been raising concerns about this issue for some time. For example, Open Democracy, an organisation that promotes independent journalism, has warned that increased concentration of media ownership leads to the risk of censorship of content. This occurs in several ways, the most pernicious of which is through advertising. Most media outlets gain around 50% of their revenue from advertising. Studies have shown that the withholding of advertising revenue has an impact on content. See the Freedom House 2019 report, or for the link between press freedom and government advertising in Africa, see the conversation.

Covid-19 puts independent journalism under greater threat

A report by the Guardian last week warns that independent reporting is under new threat as a result of the pandemic. The threat, the report states, is largely economic as both advertising and sales revenues have dropped dramatically with the spread of Covid-19. There is worry that at the end of the pandemic, only those outlets owned by large corporations and rich individuals – or those with clear political bias or government backing – will survive. These asymmetries offer potential democratic risks, such as censorship of content and overrepresentation of certain ideological views. This can lead to the defense of individualist/corporate interests over those of society as a whole or other important social groups.

International fund for independent media

The question then becomes, who will support the investigative journalists that report on corruption? Must we rely on the generosity of large corporations and philanthropic billionaires? One answer to this problem is an idea that has been around for several years: the setting up of an international fund for public interest and independent media. While such a fund may run counter to narratives about the value and fairness of market systems, there are potential anti-corruption dividends from supporting independent media and investigative journalism. Most importantly, an international fund would give voice, space, and a platform for anti-corruption journalists to publish their work.

As donors and multilateral organisations are releasing large disbursements of funds to tackle the ongoing pandemic around the world, it is more important than ever that they consider how to protect these funds from corruption. Many corruption risk management solutions rely on social accountability, oversight, and independent investigation. As a colleague and I argued in a recent publication, civil society should be a part of any anti-corruption efforts. Investigative journalists and independent media, including community radio, need to be included in these endeavours as well.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)