Blog

A case study on corrupt practices in Rwanda provides useful lessons

Rwanda is often presented as a success story for managing to reduce petty bribery in society. Yet, examining how in the capital, Kigali’s motorcycle taxi drivers deal with corrupt security officers and police officers reveals a more nuanced reality. Considering how anti-corruption policies are used by street-level officers provides a good opportunity to better understand the governance of the State and how policies are applied and transformed in practice. Such analysis may also show the way to bridging this implementation gap.

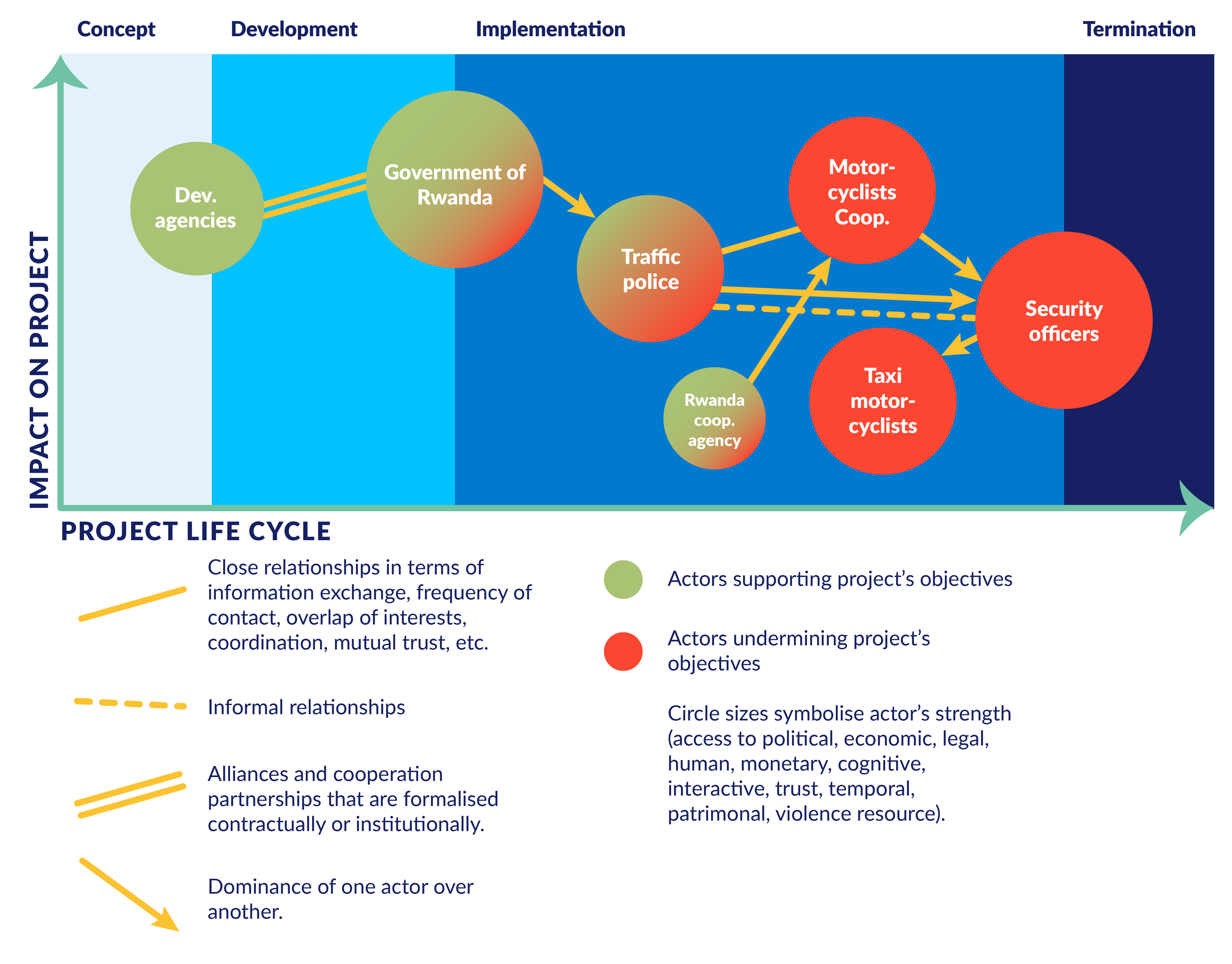

Social map of interrelationships: National anti-corruption strategy in the road sector – main implementing actors.

Petty corruption not recognised

In the everyday reality of taxi motorcyclists in Kigali, corrupt practices are common: ‘The police and the security officers are always asking us for money. We are being milked for our money!’*

Corrupt practices continue mainly because informal governance practices have caused a lack of control. In this case, the traffic police have delegated authority to enforce anti-corruption policies to security officers from taxi cooperatives. This has added another level of authority and therefore more opportunities for corruption – because the security officers are not sufficiently supervised. For example, the security officers from motorcycles cooperatives are issuing fines and asking for bribes. Both practices are totally illegal, but have the tacit support of both the motorcycle cooperatives and the police. These power relations expose the real issue: at face value, a fraud or a simple bribe belies an abuse of power, a breach of trust, and an abuse of a dominant position.

interest, these aspects of corruption are not seen in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI). As this index relies on surveys (notably the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey), CPI results may be influenced by the curtailment of free speech in Rwanda. This lack of visibility may also be because international rankings consider only an economic understanding of corruption.

Informal versus formal governance

In Rwanda, the state’s reliance on informal regulation contributes to the continuity of corrupt practices, petty bribery included. It reveals that petty corruption is part of wider issues of governance that international rankings fail to capture.

As in many other developing states, informal and formal governance in Rwanda are interlinked. This blurs the lines between lawful and illegal practices. As the state relies on state and non-state actors to jointly produce norms and order, this has become a key generator of corrupt practices. With public policies being embedded in society, the result is clientelism, favouritism, and cronyism.

The withdrawal of the police force from traffic control duties opened the door for security officers from motorcycle cooperatives to assume de facto the position of road safety regulating authority for the motorcycle taxi drivers. This has taken place without any checks or balances to curtail that authority. Corrupt practices have increased as a consequence: when interviewed in 2013, approximately 85% of the 70 motorcycle drivers stated that they had paid a bribe to the police in the month prior to the survey. By 2019, only 25% of the drivers interviewed said that they had paid a police bribe; yet 100% confirmed that they had bribed security officers. How come such a common and well-known practice may continue in a state which is supposedly corruption-free?

Unequal power relations and poor reputation

The taxi motorcyclists have tried to change the situation. They raised attention on mismanagement within taxi cooperatives through a petition to the parliament. However, corrupt practices are also supported by power relations. Modifying the distribution of power within a situation of weak democratic governance is difficult.

Moreover, the media and authorities always portray the motorcycle taxi drivers as a dangerous group. They are seen to be a community that includes criminals and is the cause of numerous road accidents. The security officers exploit this perception to legitimise the measures they take ‘to correct’ their colleagues and justify their own practices.

Of course, taxi motorcyclists can save money by paying bribes rather than expensive fines. Yet, corrupt practices represent a real burden on their earnings, as their income actually decreased between 2013 and 2019. Being the weaker ones in this power relationship, the price to pay is higher for taxi motorcyclists. The bribes are also a concern for many Rwandans who use motorcycle taxi services, as they may increase the price of taxi services. What can be done?

Bridging the implementation gap

The situation may evolve. Understanding how anti-corruption is woven into existing power relationships may help development practitioners and the Government of Rwanda bridge the implementation gap between policy objectives and their use by stakeholders. It is possible for them to achieve this if they perform a social diagnosis.

A social diagnosis aims to establish the normative and empirical expectations of stakeholders. Researchers carry out interviews and observe participants, focusing on practices and connecting them with people’s perception of their social environment. In this way, it is possible for them to better understand corruption. Accordingly, thanks to social norms theory, it is possible to identify patterns of behaviour, determine the actors’ level of agency, and measure the conditionality of actors' preferences and how they may relate to sanctions.

In the present case, it was this social diagnosis which revealed that corrupt practices did not correspond to particular social norms, as actors had not developed normative expectations towards corruption. Police officers, motorcycle taxi drivers, and security officers were following empirical expectations based on power relations and interdependencies among them. Interestingly, actors were also found to use a sort of ‘camouflage’ resorting to a context-specific vocabulary, special gestures, and cultural references. For example, motorcycle taxi drivers ask for ‘forgiveness’ by security officers and police officers, in the hope to open the way to bribery rather than having to pay huge fines.

The social diagnosis finally informs possible remedial actions in a bid to implement anti-corruption measures in the taxi motorcycle sector. It recommends promoting an improved status for taxi motorcycle drivers (changing attitudes), increasing security officers’ sense of accountability, and reducing fines (to diminish incentives for bribery).

Recommendations

Some recommendations for development practitioners:

- If development practitioners or governments are to design a realistic project, they should have a thorough understanding of the interests and aims of stakeholders. This would also help development aid managers in project implementation. Stakeholders may have divergent needs and aims. At the same time, already-established power imbalances may hamper anti-corruption measures and outcomes.

- At the strategic level (during the development phase), practitioners, managers, and governments should consider social mapping via a theory of change. This would reduce the risk of strategic failures and corruption opportunities.

- Once they have made a diagnosis, the implementation phase may introduce social change. This could be through legal leverage (new codes of conduct and control systems, new laws to create new normative expectations); information programmes (campaigns targeting social expectations that need to be changed); and/or economic actions (trying to positively impact the cost–benefit rationale towards promoted behaviours).

- Those in authority should implement adequate deterrence and sanction systems. This will avoid negative spin-offs and reduce the gap between programme objectives and effective outputs and outcomes.

For more details, see Tackling petty corruption through social norms theory: lessons from Rwanda (U4 Issue 2020:2).

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)