Blog

Fostering integrity at work: Leveraging social theory to strengthen ISO 37001

The ISO 37001 standard identifies ‘top leadership’ as a group’s body in charge to ‘demonstrate an active, visible, consistent and sustained commitment’ towards integrity. The standard also states that ‘the organisation shall develop, maintain and promote an anti-bribery culture at all levels...’ Accordingly, the core responsibility for cultivating and sustaining the culture rests with management, reflecting a predominantly top-down approach to nurturing an integrity culture.

However, is relying on management the best way to spark a collective movement towards organisational integrity? We want to explore the notion of integrity culture and consider the connection between leadership and staff – specifically, how social theory and group dynamics can influence reform processes through the power of imitation.

The relationship between ethical leadership and staff behaviour

Many in the anti-corruption field focus on the leadership team to shape organisational ideas and behaviours – often referred to as the ‘tone from the top’. International standards such as ISO 37001 explicitly endorse this approach. This concept, rooted in research from the 1950s, suggests that central figures can influence their peers. Lazarfeld’s work is foundational here, showing that leaders do not shape opinions and behaviours due to their social position or prestige, but because of their active engagement with the subject.

In the 1970s, Burns introduced the idea of transformational leadership, where leaders inspire ‘followers’ through vision and integrity. This model highlights how leaders can influence aspirations and behaviours by sharing values and acting as role models who demonstrate fairness and ethical conduct.

More recently, Trevino et al. conceptualised ethical leadership through the lens of social learning. They argue that, for leaders to affect ethics-related outcomes, they must be seen as attractive, credible, and legitimate. This requires leaders to exhibit ‘behaviour that is perceived as normatively appropriate (e.g., openness and honesty) and motivated by altruism (e.g., treating employees fairly and considerately).’

This perspective is particularly compelling as it underscores the importance of alignment between the leadership team and their staff, and the need to foster an ethical work environment.

However, we want to push this thinking further by asking: Could behavioural change within organisations be more effective by enabling collective empowerment, rather than relying on central figures?

Peer influence and chain reactions

Network theory suggests that behavioural change spreads organically once a critical mass is reached – the point at which enough individuals adopt a behaviour to trigger a collective movement through imitation. People follow social norms – shared standards of behaviour in a group – and, as more individuals adopt a new behaviour, others tend to follow.

The ISO 37001 guidance aligns with this concept, emphasising that leaders should actively promote an anti-bribery culture and ensure that staff believe in its implementation. However, while leadership is essential in setting the tone, network theory implies that group cohesion is crucial for sustaining and driving change.

Damon Centola’s research suggests that convincing just 25% of a group – for example, two team members – can initiate a chain reaction. ISO 37001 emphasises ongoing communication, mentoring, and recognition, which supports this perspective. These elements help build the social connections necessary to reach critical mass. Therefore, enhancing peer influence may be more effective than relying solely on top-down directives.

Granovetter’s threshold model shows that individuals have varying levels of resistance to change. Some readily embrace it, others have opposite preferences, and most fall somewhere in between. For example, a team member with a 10% threshold needs only one other person in the team to change before they do. Once they adopt the behaviour, those with a 20% threshold follow, and so on. Thresholds and critical mass thus vary by context. ISO 37001 addresses this by advocating for consistency in handling unethical behaviour. Further consideration could be given to creating a supportive work environment, which can lower resistance and reinforce integrity norms.

In this context, the leadership role is to set the standard, and also to cultivate a network where ethical behaviours spread through social influence. Group empowerment, backed by strong ethical frameworks, ensures that the integrity culture is sustained and self-reinforcing. But what if the key to driving change lies not in who leads, but in how people are connected within the organisation?

Understanding integrity culture through social networks

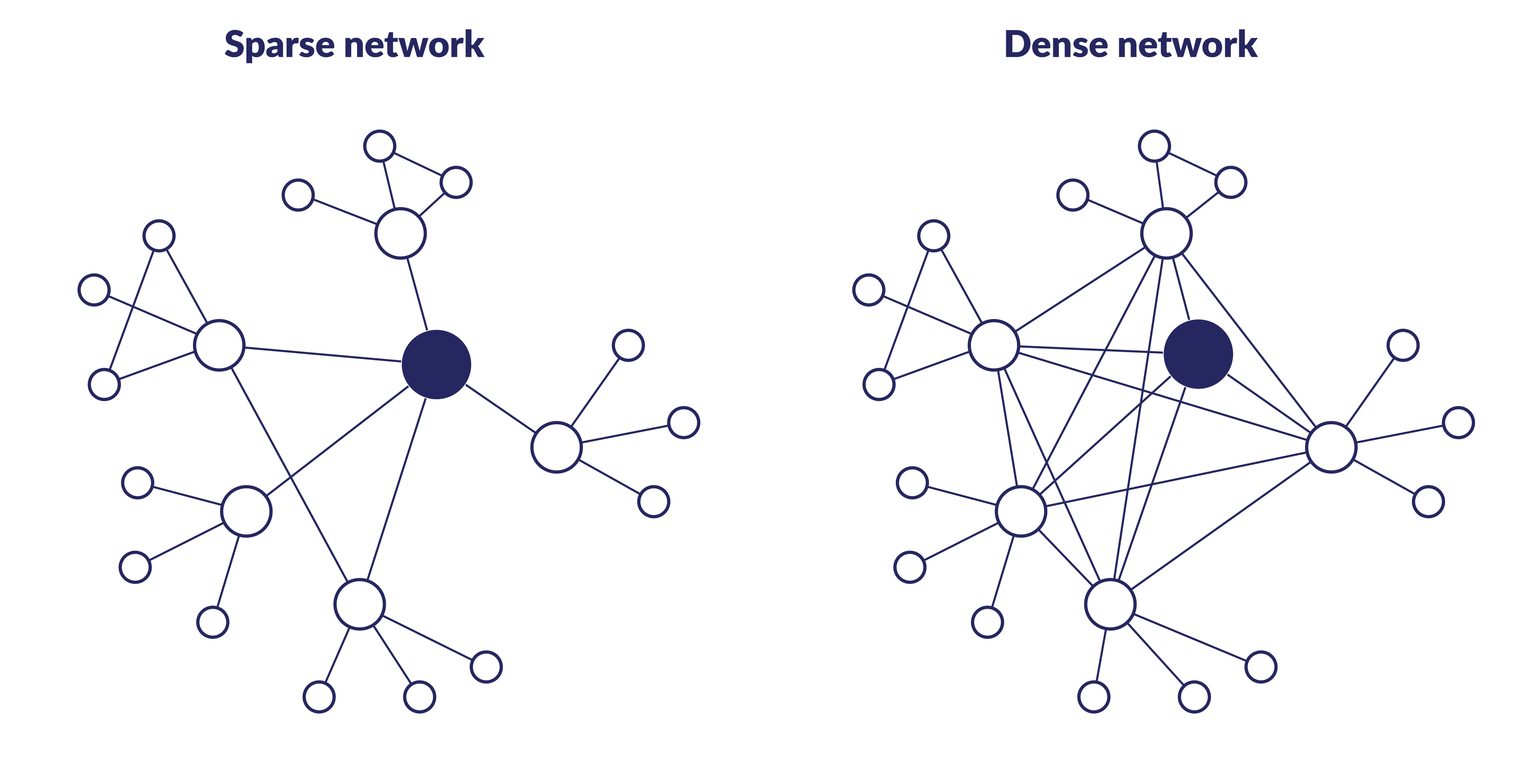

Network theory also suggests that changes rely more on relationships among individuals rather than on a central person. As illustrated in Figure 1, network density (the number of connections between people) directly influences how behaviours spread. The network doesn’t need to be centralised to be effective – changes are more likely to occur in a dense network (right) than in a sparse one (left). A central person (dark blue dot) has less influence on propagation than the overall density of the network.

Figure 1. Network density

Changes are more likely to occur in a dense network (right) than in a sparse network (left). A central person (dark blue dot) has less influence on propagation than network density.

Credit: Adapted from Nikookar E. 2021. copyrighted

This reinforces that group cohesion and collective empowerment are crucial drivers of change. By fostering a work environment that encourages these interactions, the leadership team creates the conditions necessary for integrity to spread organically. This aligns with ISO 37001 and its emphasis on embedding ethical practices across the organisation. Leadership and social networks complement one another to reinforce an integrity culture. Effective change depends on central figures and strong group dynamics. This allows us to draw valuable insights about integrity culture and the essential role that leadership plays in fostering change.

Lessons for leading integrity reforms

The ISO 37001 focus on the ‘tone from the top’ and leadership involvement can be effective when leaders actively consider the conditions necessary to foster an ethical work environment. This includes a compliance perspective that can be complemented by horizontal factors, such as peer support, socialisation at work, and the willingness of employees to report any irregularities.

As group empowerment proves to be more influential than the actions of central figures, successful implementation of ISO 37001 could benefit from adopting a collective approach, focusing on group dynamics rather than relying solely on individual performance and compliance. The role of leadership may be more beneficial in guiding the organisation in the right direction rather than taking the pilot position.

Finally, reforms require the right conditions to succeed. Change is unlikely to succeed if most individuals hold opposing preferences. Existing guidance on analysing social norms and enhancing integrity culture offers valuable insights for understanding these dynamics. At U4, we will continue to explore and advance this critical area, ensuring that the collective understanding of how social norms and behavioural change influence integrity reforms is expanded and applied effectively.

References

Brown M. E., Treviño Linda K., & Harrison D. A., 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Volume 97, Issue 2, pp. 117–134.

Buntaine M., et al., 2022, Recognizing local leaders as an anti-corruption strategy: experimental and ethnographic evidence from Uganda, GI-ACE Working paper no.17. Brighton, UK: ACE Global Integrity.

Burns J.M.G, 1978. Leadership, New York: Harper Torch Books.

Centola D., et al., 2018. Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention, Science 360, pp. 1116-1119.

Granovetter M., 1978. Threshold Models of Collective Behavior, The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 83, No. 6., pp. 1420–1443.

Lazarsfeld P., Berelson B., & Gaudet H. 1949. The people’s choice, New York: Colombia University Press.

Nicaise, G. 2022. Strengthening the ethics framework within aid organisations. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute (U4 Issue 2022:8).

Nikookar E. & Yanadory Y. 2021. How do supply chain managers affect supply chain resilience? An advice-seeking perspective. Valhalla, New York: 2021 Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management Conference, August 2021.

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. 2003. A Qualitative Investigation of Perceived Executive Ethical Leadership: Perceptions from Inside and Outside the Executive Suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5-37.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)