Blog

Corruption in the medical supply chain: lessons from the pandemic

As we pass the two-year milestone since the WHO declared the Covid-19 pandemic, we continue to learn the lessons of how the pandemic enabled corruption in the medical supply chain to thrive. The pandemic provides a real-time opportunity to identify gaps and poor practices, and test technologies and innovations that can prevent and detect corruption in the future.

How did the pandemic allow substandard and falsified medical products to thrive?

Reports of criminals cashing in on Covid-19 – with substandard and falsified medical products – began less than a week after WHO declared the global pandemic on 11 March 2020. The very earliest examples included poor-quality face masks and falsified ‘corona spray’.

In the two years since, reports of this kind have only increased. As part of their Operation Pangea XIII, INTERPOL has seized millions of substandard and falsified items, including personal protective equipment (PPE) and unauthorised antiviral medications, and Covid-19 diagnostic kits, and has closed down more than 113,000 online pharmaceutical marketplaces.

The disruption of the pandemic shook the balance of international cooperation in manufacturing, distribution and regulation in the medical product supply chain. Many countries were simply overwhelmed by the need to respond urgently to massive new healthcare demands. The structures that usually detect and respond to substandard and falsified products may have been overlooked, bypassed, or simply not prioritised.

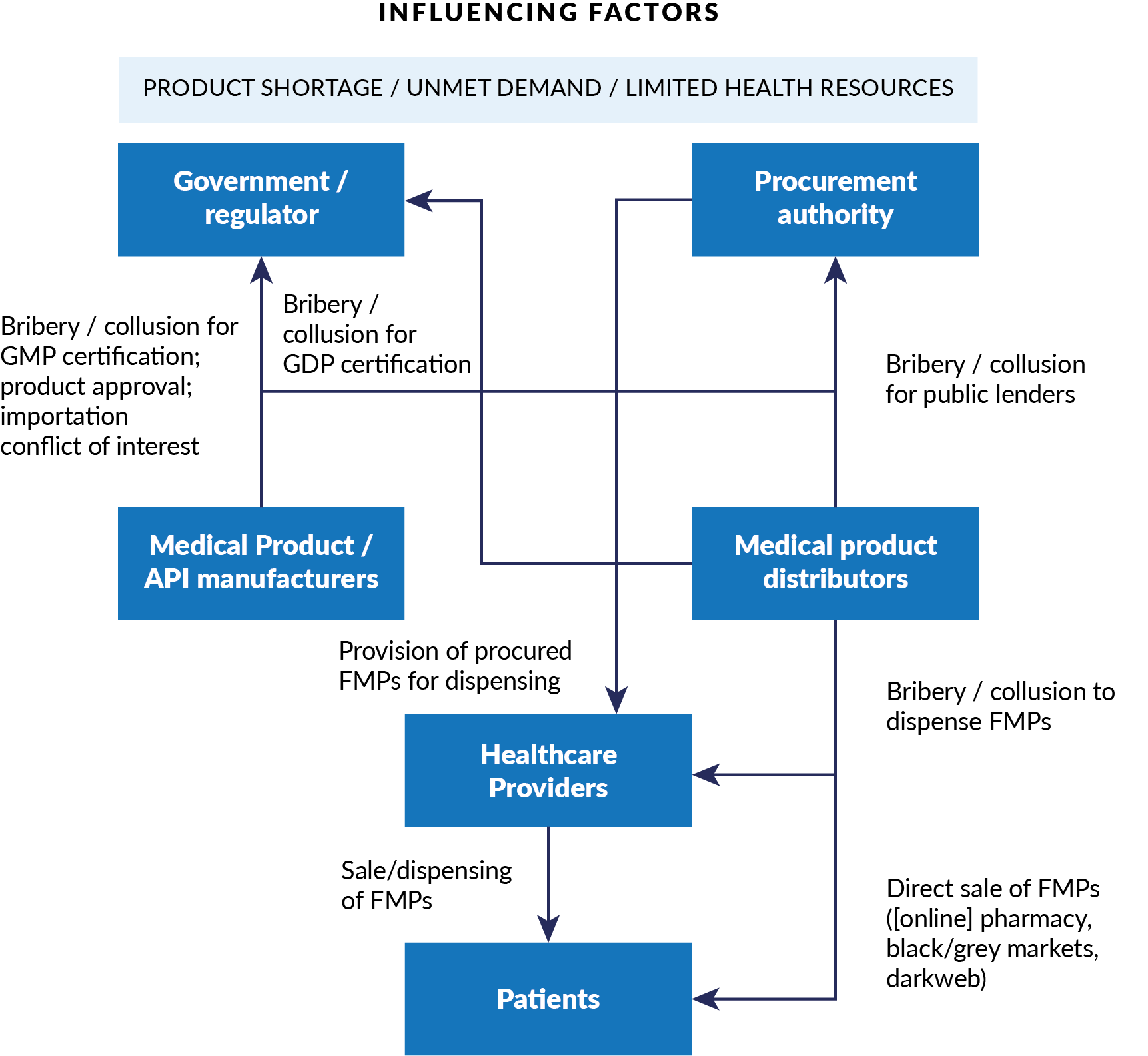

Product shortages create opportunities for corruption. Problems can be caused by poor management of existing stocks, limited regulatory capacity, increased healthcare costs, and the proliferation of misinformation and false claims, sometimes leading to new grey and black markets created by irrational and unauthorised product use. There can be challenges to national, regional and global coordination. And bureaucratic processes around funding or supply chain integrity can fail under pressure.

The pandemic can be a window into healthcare corruption

The corruption of the past two years has helped us to identify some important ways in which poor medical product quality can arise at other times. The full U4 Issue finds five critical areas where corruption can arise, both in ‘business as usual’ periods, and in times of crisis:

- Manufacturing and distribution

- Regulation

- Procurement

- High-level governance

- The health workforce

Figure 1. Conceptual model for corruption in falsified medical products

Credit: CMI–U4 by-nc-nd

Here are just a handful of examples from around the world of corruption arising in each part of the Covid supply chain, and the systems that govern it.

Manufacturing and distribution: Corruption can facilitate fraudulent certification of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and Good Distribution Practice (GDP). For example, in February 2021, the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health reported large-scale fraud and counterfeit Covid-19 vaccines in circulation.

Regulation: Manufacturers and distributors can collude with regulatory officialsto receive unwarranted certification or product approval. Perversely, national commitments to local manufacturing can create extra incentives for collusion between firms and regulators. For example, Sinovac BioTech, which developed the Sinovac vaccine for Covid-19, has been guilty in the past of paying bribes to Chinese regulatory officials to fast-track approvals for vaccines for SARS, avian flu and swine flu.

Procurement: If cost-cutting is prioritised in procurement processes, the risk of poor quality or harmful products entering the supply chain increases. Manufacturers and suppliers can also offer bribes in exchange for favours in the tender process.For example, in Zambia in 2019, the Ministry of Health awarded a tender valued at US$17 million to an unregistered company for health kits that were of poor quality and unsafe to use.

High-level governance: Government officials may become involved in corrupt schemes through personal affiliations with manufacturers, distributors or retailers. Political leaders can create product scarcity by prioritising themselves – and their families, friends and allies – when supplies are limited.In February 2021 in Peru, for instance, more than 450 people (mostly public officials, including the minister and vice-ministers of health) received vaccines intended for clinical trials.

The health workforce: Healthcare professionals can be bribed by suppliers to prescribe poor-quality or harmful products, or to supply online pharmacies and the dark web. Low-paid workers are particularly vulnerable to these approaches.In India, for example,12 Covid-19 doctors and medical workers at vaccination drives near Mumbai were found to be vaccinating more than 2,500 paying patients with saline solution, earning themselves over US$28,000.

What can be done? Lessons from the pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has proven that, to promote, improve and uphold public health, the globalised medical supply chain requires cooperative, international solutions and approaches that prioritise medical product quality and integrity.

To address the problem of substandard and falsified medical products, the U4 Issue Weak links: How corruption affects the quality and integrity of medical products and impacts on the Covid-19 response provides recommendations for governments, regulators and donors on ways to increase global access to quality medical products through innovative anti-corruption approaches that concentrate on:

- Prevention (regulation, procurement, health policy, digital technology)

- Detection (methods, reporting mechanisms, public awareness)

- Response (regulatory resourcing, legal frameworks)

And the report outlines several examples of these approaches in action:

Prevention through technology to monitor product quality

Internationally applicable standards for packaging –employing a centralised track-and-trace system – could radically improve medical product packaging. This technology exists and is accessible to all countries.

But as with any complex problem, ‘better tech’ can only be part of the answer. Digital solutions must sit within a whole portfolio of interventions, and not all technologies will be suitable in every context. Requirements for interoperability, transaction processing speeds, and privacy/security can present challenges in low- and middle-income countries, compounded by lack of financial resources and low political will.

Better detection through improved medical training and public awareness

Improved training and digital, anonymous reporting could increase the number of healthcare professionals who report products of suspicious quality. The existing US FDA Supply Chain Security Tool Kit (developed with Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation countries) could be used to train practitioners.

Media campaigns can educate the public about at-risk products and how to raise the alarm. For example, Fight the Fakes is a multi-stakeholder campaign that raises awareness about the negative impacts of falsified medicines.

Better regulation as a strong ‘last-line-of-defence’ response

National and regional legislation should be sufficiently punitive to deter criminals and healthcare workers from being involved in falsified medical products and online pharmacy supplies. To regulate medical black markets in the wake of Covid-19, Odisha in India established a state task force to strictly monitor the circulation of medical supplies.Internationally, the 22 Council of Europe countries yet to sign the MEDICRIME Convention should be encouraged to ratify the legislation as an opportunity to tackle the problem.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)