Blog

As climate adaptation takes centre stage, so should corruption considerations

Another COP (Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) has come to an end, this time in Sharm El Sheik, Egypt. Attendees were met with bold calls to reduce emissions and improve technologies to suck carbon from the atmosphere. But the message that came through even louder was very clear: there is no way that the earth can avoid a 1.5°C temperature rise, and adapting to this changing reality is an immediate concern for billions of people.

If these urgent climate adaptation efforts are to be successful, we need to think about how they might be undermined by corruption.

Addressing climate adaptation can be good for people and good for anti-corruption

Climate change adaptation, often overlooked by leaders (and hence undeservedly underfunded), might yield greater benefits for developing countries than mitigation, given that the 1.5°C warming limit is likely to be missed. Comprehensive efforts to adapt to climate change must be in place as the world suffers more climate-related disasters, such as floods, storms, wildfires and droughts. Adaptation can be cheaper than mitigation and, done right, can be less vulnerable to corruption. Adaptation tends to have more lasting benefits for people too, as it can result in vital public infrastructure being built. Turning a blind eye to adaptation reinforces climate injustice: countries that will suffer the consequences of the climate crisis are not those that caused the crisis. When it comes to adaptation though, there is still a long way to go.

Consider the case of Colombia. It ranks among the 11 countries of greatest concern when it comes to climate change, as it is highly vulnerable to its physical effects and poorly equipped to adapt. The national strategy on climate change relies heavily on the capacity and infrastructure of local governments. For instance, Colombia’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), presented at COP26, assigns 89 key responsibilities to local governments, in areas such as water, sanitation and public transport; only 30 are the responsibility of central government. If local government is to fulfil climate commitments laid out in international agreements and national strategies corruption challenges must be considered and addressed.

How corruption can hold back climate adaptation

A November 2022 U4 Issue suggests various entry points for corruption in the sectors prioritised by Colombia’s NDC.

Adaptation finance presents opportunities for the corrupt

Public procurement is a key area to focus on, since large sums for adaptation will be awarded to fulfil tasks assigned to local governments under the NDC.

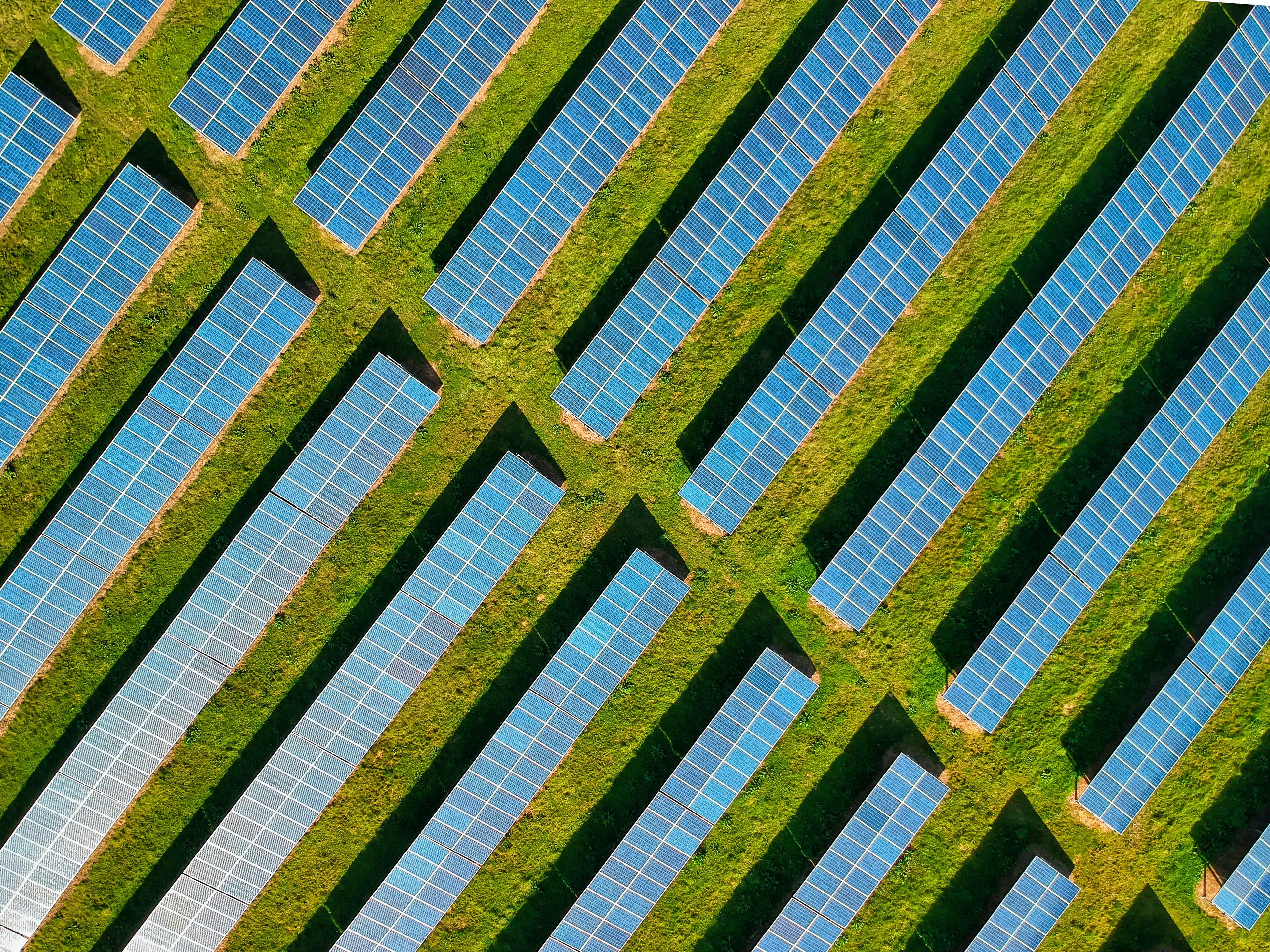

To help reduce procurement corruption, adaptation must prioritise nature-based solutions (NBSs). Local adaptation solutions should not always default to ‘grey infrastructure’ – the large concrete-and-steel projects that dominate local adaptation policy and strategy. Grey infrastructure projects rely on public procurement of construction materials and services, both of which are vulnerable to corruption risks. Price overruns, bid rigging and direct awarding of public tenders can all be used to grab public resources allocated for adaptation.

The private sector has only played a limited role in adaptation actions. The emphasis on public procurement has been met with criticism by private sector actors, who distrust the public sector as the backbone of climate change efforts. Yet the reality is that there has been very little private sector investment in adaptation. The prime reason being that adaptation does not generate profit in the way that mitigation efforts (like green energy) do. This also raises the question of relying upon market-based solutions to climate adaptation.

Limited or flawed consultations lead to poor adaptation planning

Flawed prior consultation and environmental participation have severely restricted civic space and opportunities for whistleblowing in Colombia. Absent participatory mechanisms and incentives render areas of special environmental interest, such as wetlands, rainforests and mangroves, severely unprotected, and might also jeopardise climate mitigation.

Restricted participation opens the door to undue influence. At the local level, resource-rich municipalities are also vulnerable to collusion and capture by mining companies’ lobbying, in opposition to smaller mining ventures whose environmental impact is comparatively lower. For instance, undue influence lay behind Colombia’s lengthy refusal to ratify the Escazú Agreement (finally enacted by the president in November 2022). Although the Constitutional Court has demanded Congress regulate environmental participation, there is consensus that the latter has overlooked this requirement, since representatives from polluting industries outnumber environmental defenders and community leaders’ representation in Congress.

When there is corruption, reporting and response mechanisms are inadequate. The lack of basic conditions in Colombia for corruption reporting, whistleblowing, and social accountability, especially in areas of limited state presence, remain a major concern.

Using the military to tackle deforestation is counterproductive

Finally, it is worth noting that Colombia has often preferred a state-led, militarised strategy to cope with deforestation problems. However, this leads to increased corruption risks due to endemic corrupt practices in the military itself, and a history of abuse of power against rural dwellers.

Going forward: public investment and public participation will support better adaptation plans

The reliance on market-based solutions to climate mitigation since Paris, has not brought about the changes needed to keep global warming under the 1.5°C target. Nor can we rely on private climate finance to provide the investment needed for adaptation. Adaptation efforts should be people-centred.

We need to get serious about public investment in climate adaptation to protect those countries most affected by climate change but least responsible for causing it. But to ensure that climate adaptation works for those most affected we need to address corruption challenges at local, municipal and national levels. Integrating corruption awareness and credible context-specific anti-corruption plans with climate adaptation policies and implementation plans is a prerequisite for successful adaptation outcomes.

Full and active participation by ordinary citizens, indigenous peoples, and civil society organisations can go some way towards ensuring that climate adaptation does not fall prey to corruption and networks of collusion. Support is needed to build accountability structures, strengthen local government, and create platforms for public participation to realise this goal.

Investing in nature-based solutions as opposed to corruption-prone solutions like ‘grey infrastructure’ can be another way to reduce corruption and strengthen public participation.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)